Writing a Memoir? Be Ready to Kill Your Darlings.

Hi, friends! Remember me? I’m that lady who spends all her time blogging, unless she’s distracted by something shiny, at which point she forgets to blog for weeks and weeks and weeks. (Related: I just got a new necklace and it. is. shiny.)

Oh, and also, I’ve been working on the book. That’s kept me away from here, too. I’ve been writing and rewriting and adding words and stressing about jokes and overexplaining things until finally my poor, aggrieved editor was like, “ENOUGH. STEP AWAY FROM THE KEYBOARD AND GENTLY PUT THE BABY LEMUR ON THE GROUND.”

(In this scenario, I’ve decided that I have a baby lemur. Because I’ve always wanted one).

But guess what? The book is (almost) done. At least, the writing part of it is. Just a few days ago, on the day before my birthday, my editor Colleen sent me an email which contained the following snippet, which was presumably written while sober:

…the book we have now is phenomenal, well-balanced, soulful and funny as hell with precisely the right number of poop jokes …

(For the record, the precisely right number of poop jokes is apparently a lot. A whole chapter’s worth and more.)

If I look at the manuscript Colleen started editing, and the one we have now, I find myself with two radically different works. The edited one is undoubtedly better. It flows more smoothly, it has a stronger narrative tying it together, and the jokes land strong, in precisely the way a drunk gymnast does not.

The editing process, I’ve heard, is grueling for a writer. Please don’t throw anything at me when I tell you: mine wasn’t exceptionally difficult for me. I am fairly certain that it was far harder on Colleen, who saw where my book needed to end up, and somehow had to lead me there, even though I still (despite the many times she explained it to me) couldn’t quite see the path.

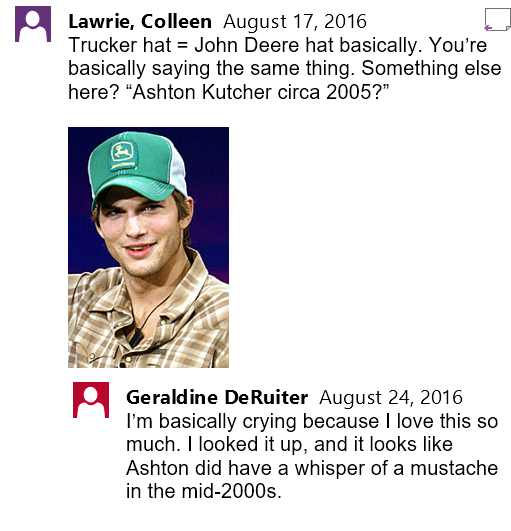

There were numerous rounds of edits, and if I look at them together, they do amount to a lot of writing and changes – but they were delivered in such manageable chunks that it never felt overwhelming. Colleen and I had conversations in the comments section of the draft, asking and answering questions, trading jokes, and pasting in the occasional image of Ashton Kutcher, circa 2005.

The initial feedback was structural and high level (whether or not a chapter worked in the greater context of the book), and with each subsequent round we’d fine tune it, until the final edits were, for the most part, tweaking of chapters or paragraphs or even the occasional joke.

Sometimes, I’d push back on Colleen’s edits – how much is really for her to say. I maintain that I was reasonable and rational, and she’ll probably maintain that I replied to her while screaming in all caps. I’d like to think that both are true.

The thing is, I never doubted that Colleen was right. I never doubted that she was leading me in the right direction. But sometimes, change is hard. Even if that change is, undoubtedly, for the better.

Writers are told the same things over and over again. Avoid cliches. Be open to criticism. Stop day drinking while openly weeping.

You know, stuff like that.

One of the most oft-repeated pieces of advice I hear? Kill your darlings.

You have to be willing to cut some of your most beloved lines. The cleverly-crafted joke, the brilliant turn of a phrase, the subtle reference to T.S. Eliot’s seminal poem “The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

I thought I was good at this. I’ve done it so many times before. I’ve done it in my own writing, I’ve encouraged others to do the same. I’d already edited this manuscript before it ever got to Colleen – several times on my own, and once or twice based on the insightful feedback that I received from my agent, Zoe, before we even pitched it to publishers.

I’m great at killing my darlings.

At least, I thought I was. And even though I knew Colleen was right, and even though she asked me to cut relatively few lines, I still agonized over it more than I should have. I winced as I deleted them. I wondered if I should have fought for more of the jokes. But even when I did, I invariably realized she was right: those lines weren’t adding to the story.

But as time went by, it got easier. And I realized that I wasn’t really killing my darlings – I was just setting them free. Liberating them from the manuscript. Those chunks of texts aren’t in the book, but they aren’t gone forever. I’ve got a repository of them. Some still make me laugh – I might use them again elsewhere. Some, upon further consideration, aren’t all that funny or good – they’ll probably never see the light of day. But when you’ve put work into something – when the story is deeply personal and yours to tell – it becomes harder and harder to let it go.

The following excerpt that I’m sharing with you today was at the start of one of the book’s earlier chapters. And while I very much liked the story I told, it wasn’t serving its purpose to tie the chapter in to the rest of the book.

But it’s still pretty funny. That’s when it’s hardest: when you have to cut something that’s isn’t bad, but still isn’t working. And while removing it from the book was relatively easily, I still wasn’t able to hit delete, so I figured I’d share it with you.

I guess we can say that I almost killed this darling. Almost.

I’ve never been all that good at the whole “forgiveness” thing.

On any given day, the majority of my mental downtime is spent rehashing old disagreements and getting surprisingly angry at things that happened decades ago.

Occasionally, when I’m staring off into space, imagining what I should have yelled to the person who stole my parking spot at the grocery store the November prior, Rand will ask me if everything is alright.

“Of course,” I’ll reply, “Why?”

“Because your expression is a little … unsettling.”

And I’ll force myself to smile brightly and tell him everything is fine, while I inwardly acknowledge that not bludgeoning that woman with a delicata squash when I passed her in the produce aisle was probably a good idea.

I’d like to think that my tendency to hold a grudge isn’t my fault, but is merely something encoded in my DNA. I remind my husband that vendetta is an Italian word.

That theory seems to fall apart, though, when you consider that my Italian-born-and-bred mother is consistently and unabashedly forgiving, even about things which she really shouldn’t be. As a child, I inadvertently tested her limits by doing a series of unforgivable things, and I suppose I should be grateful for her turn-the-other cheek nature, because to date she hasn’t disowned me a single time. Once, she really probably should have.

When I was nine or ten, I inadvertently peed all over the bathroom floor. This wasn’t the most heinous thing I would do that day. It’s just how the story begins.

To be fair, the floor peeing was accidental. It was my behavior after that which was just cause for banishment, or at the very least, she should have threatened it, driving me to an empty lot somewhere and saying, “Welcome to your new home! Get out of the car.”

At the time, we were living in a small bungalow in Florida (“bungalow” being a real estate term which refers to homes that lack both air-conditioning and central heat, have only one bathroom, and were designed by someone who thoroughly embraced the “Eh. Whatever.” approach to floor plans).

The sole bathroom was in the middle of the hallway, which meant that it was conveniently accessible from anywhere in our home, and also consistently occupied.

I suspect that on the night of the great deluge, I had been waiting for it to vacate for some time, as I remember bursting in the second it was unoccupied, and casting scarcely a glance at the bowl before sitting down. If you’ve ever had the disconcerting experience of sitting onto a toilet when the seat is lifted (and I suspect you have, because, along with yelling at the TV and attempting to solve a Rubik’s cube by just peeling off the stickers, it is part of the human condition) you know how alarmingly easy it is to drop your trousers and sit on something without actually looking at it.

I’d like to think our ability to do so has some evolutionary component – that at some point, squatting without looking around to check for snakes or bramble gave our ancestors an edge in the survival game (I’ve yet to figure out precisely how this would work, but I have drawn a few diagrams which Rand has insisted I not show to anyone.)

And so, I sat promptly down on a toilet which, I feel it pertinent to add, my mother had just cleaned. The entire little tiled room was immaculate and shiny. It smelled like a swimming pool, which is something else that, in addition to air-conditioning, we did not have while growing up. In Florida. (I bring this up not because I actually felt deprived, but more as a preemptive move against any guilt trips my mother would like to lay on me as a result of this confessional. Just so you know, mom, I also wanted a Snoopy sno-cone machine, and I never got one of those, either. So while I’m glad you didn’t disown me, let’s be fair: it’s kind of a miracle that I still love you at all.)

There I sat, on the freshly-cleaned toilet, and all went well for approximately two-tenths of a second, which is precisely how long it took me to realize that the lid was down.

The lid.

It was already too late to rectify the situation; very quickly a puddle began to accumulate under me, and it soon flowed over the edge of the lid and onto the floor, in very-unpleasant sort of waterfall.

I tried to stop peeing in a pitiful attempt to mitigate the damage but, goodness, have you ever tried to stop-peeing midstream? It’s like trying to put spray cheese back in the can. The damage has been done, and the only thing left to do is try to enjoy yourself.

Now, all of this, to be fair, could be attributed to the carelessness of childhood, a simple accident, nothing more. But what I did next was truly heinous.

I cleaned myself up, and then I walked out. I didn’t even make a feeble attempt to soak things up with a bath towel or several rolls of toilet paper, which even a drunk frat boy would have endeavored to do. Instead, I went back to the living room to watch TV, but not before shouting to my mother than I had peed all over her once-pristine bathroom.

“Wait, you did what?” my mother asked, clearly confused. A few seconds later I heard her scream from down the hall.

“OH. MY. GOD.”

At which point I just sat there and kept watching TV. I didn’t even go check on her or offer to help. I doubt I even shouted a half-hearted apology.

I just sat on the ground and stared, transfixed, at the television, until my mother emerged from the bathroom sometime later, the color drained from her face, the light gone from her eyes.

“Please,” she said, her voice hollow, “Please do not let that happen again.”

And to my credit, I did not, though I’d like to point out that if we’d had a pool, none of this would have happened because I could have just peed in there, like I did at all my friends’ houses.

My mother did not disown me on that day, or any other, and for that I’m grateful, because honestly, who would have me after that? I was 11 years old and barely house trained. Which was probably her fault, but still. The point is that she’s a very forgiving sort, and it’s gotten her nothing but grief.

And now, as I read it again, you know what I realize? Colleen was absolutely, 100% right. The story isn’t nearly as funny as I thought it was.

Trust your editor, kids. Kill your darlings.