Time Keeps Passing.

The thing about time is that it moves on, even if you aren’t ready to.

My father died last week.

While I remain stuck, trying to grasp that fact, the days keep passing. I still hadn’t processed the statement “My father died today” or “My father died yesterday” before the clock had rendered them obsolete. Part of me wants to remain in The Before – to a week ago, or ever earlier, to a time when my father was still part of the world of the living, when his life was not something to be explained in the past tense.

But my father will never do anything in the present again. I grapple with this. He’s always been far away, so even the news of his death hasn’t really set in yet. My father isn’t missing from my home because my father has never been in my home. He hasn’t been to Seattle in close to twenty years, and so his presence here remains unchanged. His photo is on my wall, his letters are in a file in my office. It’s only when I realize that I’ll never take another picture of him or receive another stamped envelope in the mail that it hits me. My father is part of the past.

I only cry when I’m reminded of this fact. Otherwise, nothing feels different.

Weird things set me off. I find a sheet of international stamps that will never be used, and I hold them tearfully. There goes another half hour. The last five days have marched on with surprising speed. Dad was always incredibly punctual; time has become weird without him in it.

* * *

The first time I see my mom after Dad died, she and I fight. She’s on the phone with someone from her internet company when I arrive, waving me into the house while pointing to the phone.

Can’t get off the line – sorry!

My dad died. I want a hug.

She doesn’t tell him she’ll call him back. She doesn’t tell him my father just died. She does hand the phone over to me, and I am unable to make sense of anything the kid on the line is saying. He thinks I am insane. He doesn’t understand why my voice keeps breaking. Mom’s computer is half-broken. Everything in her house is falling apart.

My dad died. I don’t want to talk to some kid in Phoenix about why the internet is broken.

I hand the phone back to her. After she gives up on the call, I yell at her for making me do tech support. I yell at her for asking me to do anything but cry. I storm out. She follows me and begs me not to leave. I tell her to leave me alone. I sit in my car. I call Rand, sobbing.

“It’s okay if you want to leave,” he says.

I don’t know how much time passes. I have to turn the engine on to start the heater because it’s literally freezing out. I go back inside.

I yell some more. I’ve never not been angry about this. I’ve only ever existed here, rageful, in her kitchen. She sort of yells back. My mother can make an apology sound like an accusation.

I remember that Dad was married three times. Mom has been married once. She doesn’t know what to do. She hadn’t seen him in nearly a decade. It seemed like there would be time to find some peace there. But the clock kept moving forward.

My parents in Rome in 1975. Or maybe 1976.

In the end, we both stand there in her disaster of a kitchen, crying, and I bury my face into her hair and she buries her face into mine and I realize how much smaller she is than me.

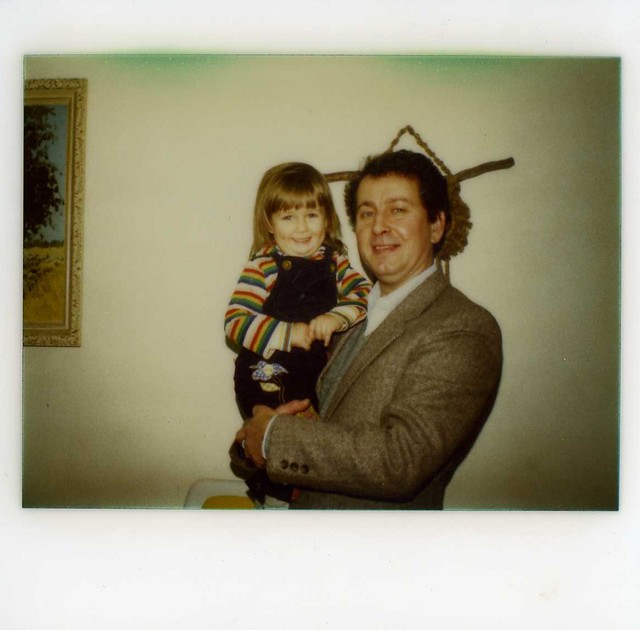

Then she starts cooking in her disastrous kitchen and I sit at a tiny table with her and talk about what she put in the mushrooms. She sends me home with a box of photos. I have been through nearly all of it. There are only a half dozen pictures of my dad in the entire lot so far.

* * *

Last night Rand and I were talking, and we both starting doing impersonations of my dad’s accent (Rand and I have been together for a decade and a half. Inside jokes get rather obscure and weird after that long.) We argued over the recipe – I thought it was one part east-coast-Jew, one part-German, one part-Russian, with a strange sort of William-Shatner-like cadence and always punctuated with either “fine” or “what the hell.” I thought that Rand’s impression sounds too much like Krusty’s father on The Simpsons. We have argued over who does it best. We each think that our impression is flawless.

But at some point Rand’s is so perfect that I ask him to stop.

“You’ll make me miss him too much,” I say. And then I realize that I’ll never hear my father’s voice again. We’ll never be able to perfect our impressions. There’s nothing to compare it to anymore.

I tell Rand how it’s weird that my father will never again answer another question that I ask him, and then we both sort of laugh because my dad never really did answer questions. He talked around them – something that I suppose, after years of working in U.S. Intelligence, became second nature. You gather information, you don’t give it out.

“He was one of the most mysterious people I think I’ve ever met,” Rand says. I can’t argue with this.

It was only in recent years that I really got to spend time with my father. Just one more thing that traveled offered: the opportunity to understand those closest to me. Rand would accept conference invitations to Germany whenever they came his way – “We can go see your dad,” he’d say. Without my husband, I don’t think I’d have known my father as well as I do. We didn’t get along when I was a kid. My dad didn’t know how to act around children. I suspect because he never really had a chance to be one himself.

But Rand was always quietly putting him into perspective for me.

“He doesn’t demand things of you,” he’d remind me. “He never expects you to do things a certain way. There are no strings attached.”

My father, for all his misanthropic qualities, was accepting of everything in my life. This was no small thing, and Rand understood this. I think that’s why my dad liked him so much.

“We’re going to be family soon,” my father said dismissively to Rand when my beloved and I were still dating. This wasn’t a statement of affection (my father didn’t make those). It was simply a statement of fact.

In his last few months, I took advantage of the guard he’d had to let down as a result of his illness.

“I love you, Dad,” I’d tell him.

Normally, my father’s response to this would be a simple, “Fine.” But in his last few months, it was, miraculously, this:

“I love you, too.”

I’m terrified that the memories I have now are the clearest they’ll ever be. From here on out, they’ll fade. I’m trying not to reduce his voice to a caricature of what it was. I’m trying not to rewrite the narrative of who my father was. As time passes, I don’t know how much of that I’ll be able to preserve.

“It always felt like time stopped in that village where he lived,” Rand said to me last night. “Each day lasted an eternity.”

I hope that was true for Dad, at least during his healthier days. I hope that my father had an eternity in that village. And I hope that in that infinite span of time, he even found an occasion to smile now and then.

For me, I’m just trying to get used to the clock moving forward without him.