Museo Fallero, Valencia, Spain

Do you remember when I told you about Las Fallas? The festival in Valencia where giant sculptures of plaster and wood are meticulously constructed over the course of a year, then rapidly burned down on one Bacchanalian night while crowds of drunken onlookers cheer?

A visual reminder.

A selfie from March of 2015 with the smoldering remains! Frankenstein was so wrong – FIRE GOOD.

Pyromania isn’t really my thing (I’m more self-destructive than outwardly destructive … ba-da-dum!) but I still enjoyed that night a lot. I appreciate any ill-advised celebration, so if you’ve got a bunch of inebriated people screaming just a few feet away from pyrotechnics and open-flames, and you throw in some churros for good measure, I’m totally in.

But there was still something painful about watching those enormous sculptures go up – literally – in flames. Each of the larger structures was surrounded by ninots – smaller sculptures of people that often parodied celebrities or political figures. The ninots were generally quite sweet-looking – soft-edged, smooth-skinned and big-eyed, each one felt like an homage to Disney – but they were often placed in obscene poses or in various states of undress and I stared at these with morbid fascination as they were doused with lighter fluid and set aflame.

Sometimes, a small sculpture might escape its fiery end – we saw a few that were dragged off into the night by well-meaning, drunken Samaritans – but for the most part, they all burn, and so the Festival of Las Fallas is, by design, a sort of ephemeral experience. You really have to be there to appreciate it.

Last week I wrote about having to kill my darlings as a writer, but even when I do, those chunks of work exist in some forgotten file on my computer. But the fallero artists? They really kill their darlings. They burn them straight to the ground.

Which is why the Museo Fallero (or Museu Faller) – the Museum of the Fallero artists – is such a unique thing. Because it attempts to capture something which, by the design, wasn’t meant to last.

The Museum is central Valencia, not far from the Ciudad de Las Ciencias, and easy to miss unless you know that it’s there. The facade is plain, the building small, and when I went I had the place almost entirely to myself.

Inside are ninots from various Las Fallas celebrations spanning decades. Almost every single one is a modern reproduction, based on photographs and illustrations- the originals were burned. (Please note that some of the following photos are sort of not suitable for work. While there is no actual human nudity, there is some ninot nudity, and some sensitive imagery.)

Something about how some of the figures were stylized suggested the era in which they were made. I found that I could almost attribute a time stamp to several of the ninots, and I tried to guess when they were made without peeking at the adjacent placards.

This was created in the late 1940s. I originally thought it might have been Luis Companys, the President of Catalunya who was executed during the Spanish Civil War, but I don’t think it is.

This hippie couple was from 1971.

Looking at some of them with through the lens of 2016, it’s hard not to cringe. Some of the ninots were strange, some were gaudy, some were just plain offensive. But my biggest issue was that I had not context in which to place a lot of them.

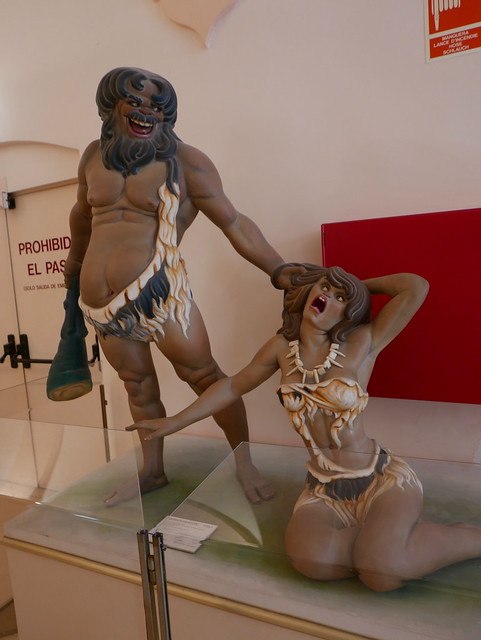

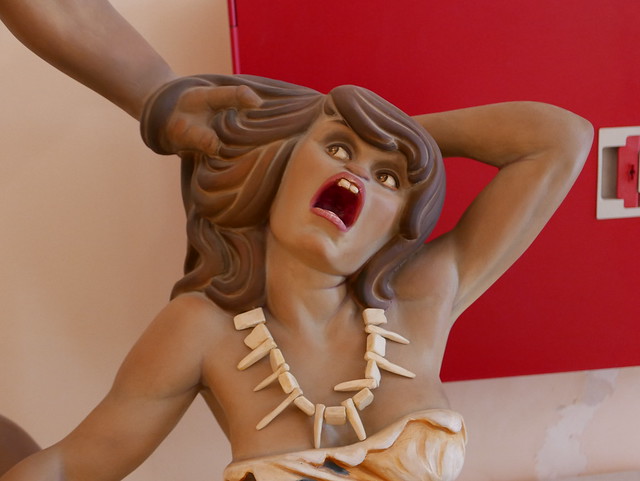

For example, check out this reproduction of a piece originally produced in the late 1950s, entitled “Prehistoric Marriage.”

Totally appalling, right? But here’s the thing: that might have been the entire point, even in 1957. This ninot might have been a testament to the women’s movement, and not an indictment of it. It might have said, “Look, look at things haven’t changed, even now, in 1957.”

And then it is burned to the ground. A rather profound and powerful statement, right? But without context, it’s impossible to know.

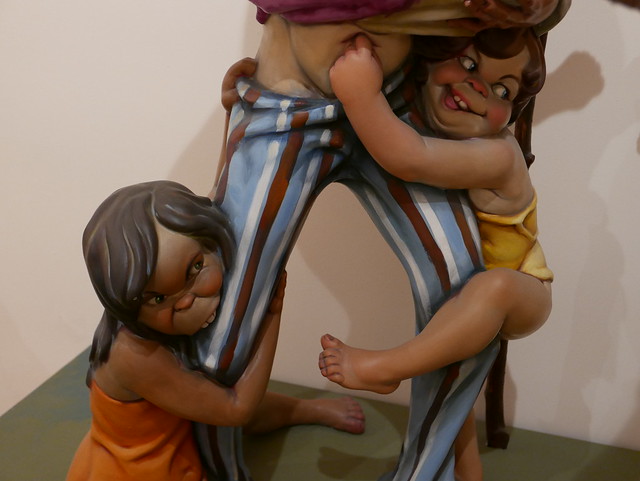

Or this one, originally made in the early 1960s (again, most of the ninots on display were modern recreations), of two parents completely overwhelmed by their many children. It’s a funny scene, but given that birth control and contraception was illegal in Spain, beginning just after Franco rose to power in 1941 until 1978 (three years after Franco’s death), there might be more to this than simply the humor of it. It might be stating a very urgent need for family planning among Spanish citizens.

And again: it was burned to the ground.

Then there’s this ninot, reproduced from one sculpted in 1969. It is a pile of naked toddlers. Make of that what you will.

The point is, being able to view these figures with some awareness of what was going on when they were created is really important. And seeing them, decades later, and as a foreigner, means that is a very difficult thing to do. The entire point of ninots is that they are incredibly timely – parodies of the current political and cultural system. To remove them from that is to rob them of meaning.

I can’t remember when this one was made. I just remember loving the expression on her face. It’s an amazing mix of contentment and boredom.

In addition to the reproductions, the museum is also home to a few old ninots that somehow missed the quemada – the burning. They were now protected behind glass – an act which sort of seemed absurd. Like a destiny unfulfilled.

This tiny figure of Mary Poppins and Bert was from the 1960s.

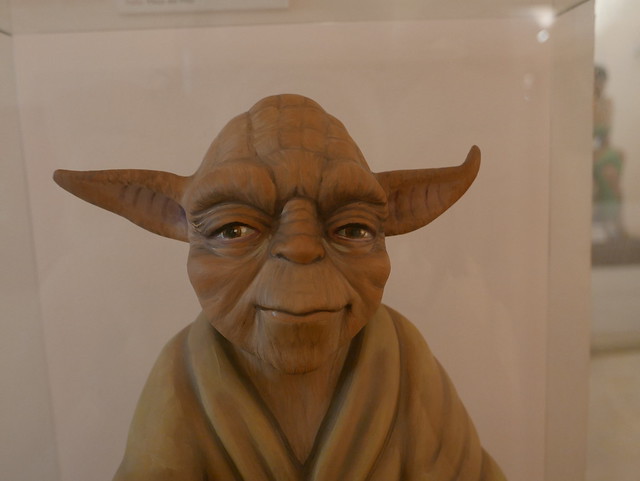

Yoda dated back to the early 80s.

Hey, you survived getting torched? Great! Now you are precious!

And some were nearly impossible to attribute a time or place to. Like this rather exceptional sculpture of Cervantes, for example, writing at his desk, a miniature Don Quixote manifesting straight from his pen. It was created in the mid-nineties.

Or this one, in which the children are dressed in traditional Valencian outfits, but the little boy is playing a handheld video game. And notice how pose of the little girl mimics the one of the figure in the poster behind her.

Or this one, which is awesome and creepy because it combines two of the most terrify things on the planet: clowns and chimps.

This is a nightmare. An actual nightmare.

Fantastic, but they could have been made at virtually any time in history, and so they felt less shocking to me, and also less relevant.

I wandered through and watched as the ninots spanned from the bawdy …

To the beautiful …

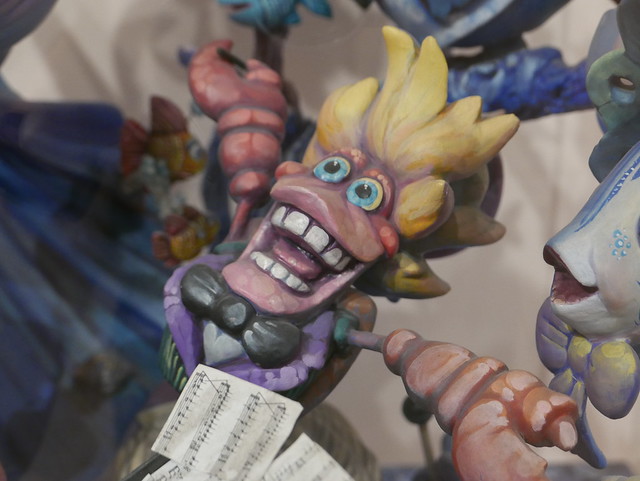

To the copyright infringing …

Are we supposed to pretend this isn’t Sebastian?

While some of the stuff was, well, just plain weird.

Some of the ninots were far away from human so as not to be creepy, but others bordered on the edges of the uncanny valley (for more explanation of this concept, check this out. Basically, with humanoid objects, there’s a certain level of resemblance to humanity that we are okay with. But when that level gets too close to being human, that creeps us out mightily.)

The result was unsettling.

GAH!

And despite all of that? Despite the creepiness and the cringing? I thought the Museo Fallero was pretty outstanding. Visitors are able to get a close-up, rarely-seen view of the ninots, and of a rather fascinating aspect of Valencian culture.

Even without perfect context, that’s a rather exceptional thing.