Choeung Ek Genocidal Center, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Note: Today’s post goes into detail about the brutality of the Khmer Rouge, and specifically what happened at the Killing Fields. There are also images of human remains (mostly bones and skulls) towards the end. I just wanted to let you know beforehand. Also, I’ve listed this under tourist attractions, because I guess it is, but that just feels … wrong.

It is an astoundingly beautiful and terrifying place.

On our first morning in Cambodia, we visited the Choeung Ek Genocidal Center. It was a 45-minute tuk-tuk ride from our hotel in Phnom Penh (ours cost us $20 for pretty much most of the day). Once we got out of the city, a good stretch of the journey was on dirt roads. Closer to the center, we found paved roads again – at least, partially. A raised slab of smooth cement had been laid upon the dusty ground, leaving a sharp drop on either side that necessitated a skill of steering so that we wouldn’t go tumbling off.

Why bother to pave road that you aren’t going to use?

Downtown was a whir of scooters and tuk-tuks, but here things were noticeably calmer. The sky looked bluer. The cows looked cowier.

Wait, can a cow look cowier? Maybe.

A short while later, we arrived at Choeung Ek. The center is located at one of 20,000 mass grave sites that dot the country and comprise the Killing Fields. It was at places like these that the Khmer Rouge killed millions of Cambodians for reasons both arbitrary and absurd.

When we arrived, the scene was idyllic. Almost ludicrously so. The sky was bright blue, the grass a brilliant green. Butterflies flitted through the meadows and bushes. The only sounds were the chirping of birds and the buzzing of insects.

There was no wind, and the air felt too still – heavy with the perfume of flowers, and weighted down by something something else inexplicable. I’m not inclined to thoughts like this, so I hope you will understand what I mean when I say that it felt haunted. Not in the traditional definition – I don’t mean to say that it was frequented by ghosts (though, perhaps, that’s not much of a stretch to imagine) – but that it felt tormented by the atrocities that took place. Though the trees are the only witnesses left, you can almost feel what happened here.

It is both incredibly peaceful and terrifying. A combination of feelings that I had never experienced until visiting Cambodia.

Nicci and I took the audio tour ($6); virtually everyone else we saw was doing the same. There are many signs throughout that request that guests be silent. This is an easy rule to follow. It wasn’t the sort of place where you felt like talking.

It was here, at this place, and literally thousands others like it, that the Khmer Rouge would murder Cambodia citizens who were believed to be impure, or who were considered threats to the new Communist regime. The criteria were easy to meet. People were killed for being Chinese or Thai (or for having Chinese or Thai ancestry). For being Muslim or Christian. For having a college degree, for speaking another language, for wearing glasses.

Basically, anything could get you killed under the Khmer Rouge.

Many victims would arrive from Tuol Sleng Prison (Nicci and I would visit there later in the day – it merits its own post). Others had already succumbed to torture there, would die still chained to the beds on which they’d been interrogated (when the Vietnamese army arrived, the Khmer Rouge had left in such a hurry that there were still bodies shackled to the bed frames). Some survived, often by making false admissions of guilt to end the torture – claiming that they were CIA spies, or agreeing to whatever preposterous allegations had been leveled against them.

Then they’d be carted off to the Killing Fields, arriving in the dead of night, blindfolded and by the truckload. They were told that were going to be “relocated” to a new home.

In some perverse sense, I guess this was an accurate statement.

There are signs everywhere explaining the different sites. They are short, factual, and all together horrifying.

The lie was constructed to keep everyone calm as they marched, unknowingly, to their deaths. Most would be killed that night. They would be led to the edge of a massive pit – a mass grave – and killed there, so that their bodies would fall directly in. The Khmer Rouge didn’t want to waste bullets, so they were creatively sadistic in their means of slaughtering. Hatchets, leg irons, knives, gardening implements – they killed with whatever was handy.

The depression left in the ground from one of the mass graves.

Pavilion placed over one of the mass graves.

Some innovative sociopath soon realized that the branches of the sugar palm were serrated, like a knife. I don’t think there’s any need for me to elaborate further.

The occasional victim was not quite dead when they were flung into the graves, and a dousing of DDT served to finish them off, and to cover up the smell of decay.

The murders took place during the night. A loud, whirring generator was run, and revolutionary music was blared out of loudspeakers to drown out the screams. The audio guide recreated what this must have sounded like – I listened.

It literally might have been the most horrible thing I’ve ever heard. Removed from the act by decades, standing in the middle of the quiet field, in the bright sunshine, it was still terrifying. I heard it for days afterward.

In hindsight, I realize I kept following Nicci all around the Center. I didn’t want to lose sight of her, to feel alone in this place.

The auditory cover-up seemed to work quite well – not even those in neighboring farms knew what was happening. Or perhaps they knew, but really, what recourse did they have?

Soon, Choeung Ek became overrun, and the Khmer Rouge officers literally couldn’t keep up with the amount of killing required of them. They were murdering up to 300 people a day. They had to build a detention center to hold the prisoners that they didn’t get around to butchering on the first night. It was crowded and windowless.

Choeung Ek had once been an orchard and a Chinese graveyard. If you look closely, you can see the broken remains of the tombstones, next to the large depressions in the ground where the mass graves had been. Look closer still, and you might see something else – traces of the victims of the Khmer Rouge. These remains are often uncovered by the downpours of the rainy season. Workers at the center gather them up and place them in glass shrines along the walking path – chips of bone, teeth, scraps of clothing.

Remnants of a Chinese grave.

I cannot tell you how ridiculously tiny this pair of shorts was. They had belonged to a small child. As I mentioned last week, the Khmer Rouge did not discriminate by age. They killed children and infants alongside parents, fearing that if the little ones were allowed to grow up, they would want revenge.

Fact: If child-murdering is part of your ideological doctrine, YOU ARE ON THE WRONG FUCKING SIDE.

The audio guide was rather detailed in how the children were murdered. If you want to know more, you can look it up on your own. I don’t want to go into the tales of death more than I already have.

Offerings left at one of the mass graves.

Offerings hung from a tree, for the child victims of the Khmer Rouge.

Towards the back of the facility is a large lake. There are remains of more victims at the bottom, but the workers at Choeung Ek have decided to leave them there. It would be too difficult to remove them.

“There are still people in there,” Nicci said to me. “Yeah,” I replied. I wasn’t sure what else to say.

Nearly 9,000 men, women, and children were killed here. And there are 20,000 more sites like this throughout Cambodia. It’s believed that not all the mass graves have been uncovered.

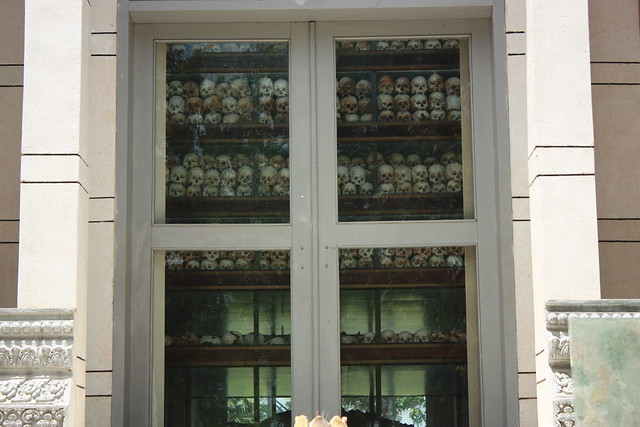

The end of the audio tour will wind you back around near the center of the facility, to the Buddhist stupa that stands guard over the grounds. It is a modern structure – built in 1998, and one of the few that sits on the property (the rest of the buildings were dismantled after the fall of the Khmer Rouge. Survivors had nothing, and they used whatever they could find – pulling down buildings and structures – to try to rebuild their lives.)

At first, I didn’t realize what was inside.

Then it came into focus.

There are more than 5,000 skulls inside the stupa, belonging to the victims of Choeung Ek.

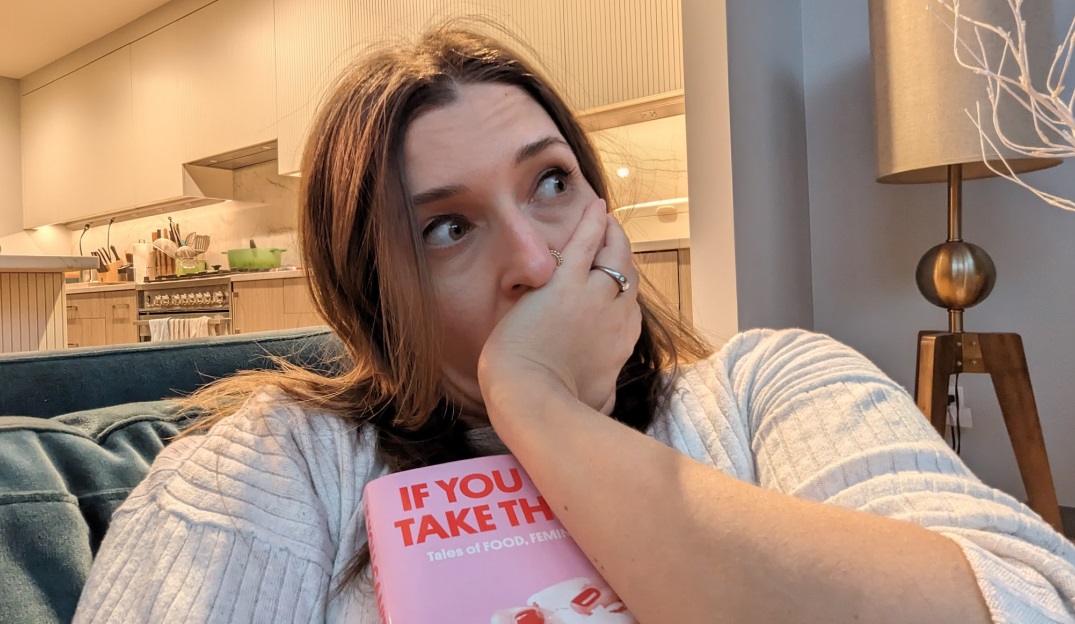

I wasn’t sure whether or not to take photos. And if I did take them, whether or not I should post them. But Nicci said something to me, with a sort of clarity of understanding that eluded me (I would notice, as the trip progressed, that she often had this: an ability to see things that I could not. It is a good quality to find in a travel companion. It’s a good quality to find in anyone, really).

“They were put here for a reason,” she said. “They want people to know what happened.”

So I crossed the threshold, onto the narrow walkway that wound around the inside of the stupa. And I took photos of the dead.

The skulls were marked with small stickers, color-coded according to how the victims had died.

I’m not particularly religious. But I stood there and, recovering Catholic that I am, I crossed myself. Because I wasn’t sure what else to do.

We rode back to town in relative silence. There wasn’t much to say. I wondered how, exactly, we’d go on with the rest of our day, after having seen all we had.

Then I realized what a bullshit thought that was. Because we had simply visited the place, we’d simply heard the stories. But there were people who had been there. Who had actually seen it. All of it. They’d lived through it.

Virtually every single person we’d encountered had been scarred by the Khmer Rouge in some way or another. And they all carried on. Each and every damn day.

Leave a Comment