A Not-So-Brief History of Apartheid in South Africa

Doorway at Robben Island, where numerous political prisoners were held during apartheid.

–

After we returned to Cape Town, Rand and I took a township tour. I think, without hyperbole, it may have been one of the most significant experiences of my life. I very much want to tell you about it, but it’s impossible to talk about the townships without first talking about apartheid in South Africa first, and its miserable legacy.

And that is going to take this entire post, at the very least. The recap of the township tour will have to wait until next week.

As with my coverage of Irish history, I’d like to note a couple of things: I know relatively nothing about South Africa’s past. I’ve done a bit of research, and I’ve put it down here as best as I could. I have no doubts that I’ve gotten plenty of stuff wrong, accidentally omitted a great deal, and may have missed the point entirely a few times. This was obviously not my intention. If you find a glaring error in the post, I will kindly ask that you make your corrections in the comments section below, along with a source pointing to the correct information.

With all of those caveats in place, I’d like to tell you about apartheid. At least, as best as I understand it.

Apartheid officially came to pass in the 1940s, but the foundation for it was laid long before that. Racial segregation in South Africa had existed since colonial times, when Dutch and British factions controlled the country (there were several wars between the Dutch and Brits over control of South Africa starting in the late 1800s and extending in to the 20th Century. Forgive me, but I find that there’s something kind of perversely funny about two countries fighting over a third country that probably wanted them both to piss off). In 1902, a peace agreement was signed, where the Dutch republics in South Africa swore allegiance to the British Crown (which maintained control of the country until it became its own republic in the 1960s).

The peace agreement allocated a lot of rights to Dutch citizens of South Africa, but it didn’t change circumstances for people of other races. Even prior to Peace Agreement, there were laws on the books that enfranchised whites and oppressed anyone who was black, Indian, Asian, or “coloured.”

Note: I know that if you are anything like me, the phrase “coloured” in reference to a group of people probably makes you cringe. The term (without the superfluous “u”) is out-of-date and pretty damn offensive here in the States. Indeed, in most parts of the world, it isn’t used, ever. Except in South Africa. There it is used quite often, and to the best of my understanding, it isn’t considered offensive. It refers to anyone who is of a mixed racial heritage, whose ancestry extends back to Europe as well as to the indigenous tribes of South Africa (or parts of Asia, like Indonesia). Here’s a complicated but interesting definition of the term by a man who self-identifies as coloured.

A variety of bills were passed in the early 20th century that limited the rights of non-whites in South Africa. They were not allowed to vote or hold political office, were limited in where they could make their homes (pushed into what were essentially reservations, they were not allowed to live or purchase land outside of these areas), and had restrictions placed on what kind of education they could receive. If you weren’t white, you were paid very low wages, were prohibited from holding certain jobs, and had harsh taxes imposed on you for the paltry money you were able to earn.

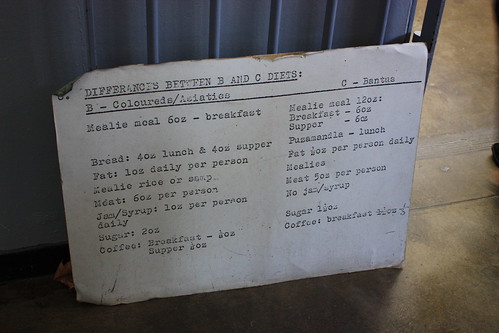

While circumstances were pretty bad across the board if you weren’t white, blacks were definitely the most disenfranchised group in Africa during this time. This sample menu from the prison on Robben Island illustrates the notion pretty clearly. Notice how the menu at right for Bantus (a kind of generic term given collectively to native peoples of Africa during the time) is radically different than that for Asian or Coloured prisoners:

There isn’t even a hint as to WHY it’s different. It’s like they KNOW they’re being racist assholes, you know?

–

And then there were the passes. This was a throwback to slavery – when slaves were required to carry passes any time they were traveling without their masters. The Pass Laws required non-whites to carry passes – a form of identification which denoted their race and personal information – that listed which areas in the country they could travel to and which areas were prohibited (activist and politician Robert Sobukwe was imprisoned on Robben Island for being in an area that was off limits according to his pass).

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s talk about when apartheid officially began. Which requires us to go back in time to 1948.

That was the year that the Nationalist Party became the ruling party in South Africa (they would retain control of the country until 1994). They established a system of apartheid – basically, racial discrimination was now institutionalized. All the oppressive laws that were still on the books from earlier in the century were enforced, and in addition to that the government had further plans to not only disenfranchise non-whites, but to segregate all the races.

The Nationalist Party felt that South Africa wasn’t one country – it was several mashed together, each correlating to a different racial group: blacks, whites, Indians, and Coloureds. Through a course of logic that I can’t really wrap my head around, because it’s not even remotely logical, they decided to split the population of South Africa up according to those different groups. The black population was divided even further, assigning people to specific Bantu nations.

This reassigning of citizenship gave the government the opportunity to strip non-whites of virtually all their rights by claiming that these people weren’t really citizens of South Africa (their right to vote as well as their passports were, on this basis, revoked). They were now considered residents of whatever new nation their appearance had dictated.

Of course, that didn’t mean they had any rights in these new “nations,” which fell under the control of the government of South Africa.

In order to enact their new plan for South Africa, the Nationalist Party rolled out a series of measures aimed at segregating the communities. Their first two major pieces of legislation passed would become known as the Pillars of Apartheid.

The first pillar was the Population Registration Act of 1950. Under this law, everyone living in South Africa would be classified according to race. The guidelines for how to classify people are ridiculously vague:

A White person is one who is in appearance obviously white – and not generally accepted as Coloured – or who is generally accepted as White – and is not obviously Non-White, provided that a person shall not be classified as a White person if one of his natural parents has been classified as a Coloured person or a Bantu …

A Bantu is a person who is, or is generally accepted as, a member of any aboriginal race or tribe of Africa…

A Coloured is a person who is not a White person or a Bantu …

This perverse exercise, as I mentioned above, was how people were assigned to different racial groups, and subsequently separated. But here’s where is gets really effed up: if your physical attributes did not easily fit into a category, a board would convene and decide what race you fell into based on your appearance. This meant that families could be split up because the members had been classified into different racial groups (and therefore had to be segregated from each other). You could be sent to a Bantu nation that you were completely unconnected to, simply because, according to a panel of white people, you looked like you belonged there.

Effed-up pillar #2 of Apartheid was the Group Areas Act, which led to the separation of the different races. This law dictated where people could live, according to the racial categories into which they had been classified. This led to the formation of “white areas”, “colored areas”, “black areas”, etc (and further subdivisions within the black areas according to Bantu origin). This law was later used to relocate and displace people from their homes.

It also served as an excellent tool for the government to continue oppressing people. Any time a non-white community grew too large, or too prosperous (rare, given all the laws to prevent non-whites from earning a decent wage), or the land on which it was resided was deemed too valuable, the population would be relocated, their homes destroyed, and the area would subsequently be declared as “white”.

District Six in Cape Town, a portion of the city where a large black community lived, was destroyed under this law, the inhabitants were pushed to the outskirts of the city into townships. With virtually no resources at their disposal or opportunities to earn a decent wage or get an education, the population remained in abject poverty, crowded into tiny shacks. (Note: Rand and I did a tour of a museum dedicated to District 6 during our township tour. More on that next week). This legacy of poverty and oppression still remains, and the situation in many of the townships is quite dire.

Old street signs hang in the District Six Museum in Cape Town.

–

Sophiatown, a thriving black community near Johannesberg, was also destroyed under this law, as it was feared that the population there might rise up against the government. (And just when you thought it couldn’t get any more awful, the town was declared a white area and renamed Triomf – Afrikaans for “triumph”.)

There was plenty more legislation beyond these two acts. Here’s an excellent summary of some of them, but I’ve listed a few highlights below:

- Suppression of Communism Act – this law was originally created to outlaw the Communist Party of South Africa (which was considered a threat to apartheid), but eventually it was used to quash any political organizations which were a threat to the ruling party and the status quo. The wordage was incredibly vague, so it could be applied to nearly anyone. Nelson Mandela was arrested under this law.

– - Immorality Act – Sexual relations between blacks and whites were already illegal in South Africa according to the Immorality Act of 1927. This law expanded upon that original one; sexual relations between whites and anyone who was non-white (e.g., Asian, coloured) were now illegal as well.

– - Separate Amenities Act – these were the South African equivalent of Jim Crow laws; they dictated that certain areas could be specified for people of certain races

– - Bantu Education Act – this one makes my blood boil, because I would like to think that children are exempt from institutionalized hatred. Under this law, non-white schools (because remember: everyone was already segregated by this point) had to teach a racist curriculum as decreed by the government. Non-white children were taught that traditional Bantu cultures were base and inferior; and that they would be limited in their achievements by their race.

– - And of course, let’s not forget: non-whites had to carry passes, couldn’t vote, earned meager salaries, were not given access to decent schools, were subject to substandard health care, were prohibited from holding office, and forbidden from working a vast number of jobs (including a variety of skilled trades). They could be jailed (often indefinitely) for the smallest of infractions, and many were.

This went on for literally decades. Despite the governments best efforts to quash them, anti-apartheid organizations began to appear. There were a number of significant protests and uprisings (including the Soweto uprising, which had numerous casualties, many of them children, at the hands of the police). The brutal treatment of those who spoke out against apartheid – many were tortured or executed – began to get global attention.

Pressure, eventually, mounted from international sources. The UN denounced South Africa’s policies in the 1970s, and even voted to kick the country out, but major players like the United States, France, and the U.K. – all trading partners with S.A. – vetoed that decision. Trade was also the reason why later embargoes and economic sanctions against the country failed. By the late 1980s, though, even South Africa’s trading partners had had enough of the injustices (It only takes us a few decades to come to our senses, even when it’s not entirely in our economic interests to do so) and a variety of sanctions were placed on the country.

There were also a variety of other boycotts – cultural embargoes- from all over the world. A large community of celebrities prevented their films and products from being available in South Africa, and the country was banned from all international sporting events (including the World Cup and the Olympics – a ban which was not lifted until 1993). This last act was not merely symbolic – many have claimed the sporting boycotts helped end apartheid as it let the people of South Africa know that the international community would not tolerate what was happening there.

Ultimately, though, change had to occur from within. During the 1980s, the president of South Africa, P.W. Botha, was … how can I put this delicately? I’ll just use a quote from his obituary in The Guardian:

(He) was gradually exposed during his long decline as one of the most evil men of the 20th century, committed to state terrorism, war and murder to thwart black majority rule.

Or, as I would put it: he was a huge dickbag. The internal unrest within South Africa panicked him. He placed the entire country under a state of emergency, which essentially gave the government the right to detain any person, indefinitely, without cause. Thousands were detained. Hundreds were tortured. Others were executed.

Barbed wire atop a wall at Robben Island.

–

While he repealed some old apartheid laws that had been on the books for decades (including the Immorality Act and a relaxation of the Group Areas Act) in hopes of appeasing the population, he still refused to give blacks a right to vote, refused to negotiate with African National Congress (Mandela’s party), and even ordered air strikes against the offices of exiled ANC leaders.

After a mild stroke he was forced to resign, and was unexpectedly replaced with F.W. de Klerk, who had been the Minister of Education. Though he was not previously known as being particularly progressive, it was under de Klerk that apartheid ended. He released Nelson Mandela, called for a new constitution that gave everyone -regardless of race – a right to vote, and fostered negotiations between the ANC and his own political party. In 1993, he and Mandela were both jointly given the Nobel Peace Prize.

Aaaand, you know what? After 2,500 words, I’m pretty much out for the count. And while I’d like to end on a happy note and say that now things are absolutely wonderful in South Africa, that would be grossly inaccurate. Apartheid left a lasting legacy there, which is evident on the dusty streets of its many townships.

But that’s a story for next week.

Leave a Comment