The War

This past Christmas, I was down in California, on the front lines of the ongoing war that takes place amongst my family members. It’s been happening for years, punctuated by little battles every time enough of us get together.

We’re all participants, though many of us don’t know it. We become casualties as a result of some slip up in our actions, often without realizing what we’ve done.

We might put parmesan on seafood pasta (as my brother did one year, which elicited a gasp from my aunt), or we might make our lasagna with ricotta instead of bechamel sauce. I was guilty of the latter several years ago. It was the night before my Uncle Walter’s funeral, and Rand and I had stayed up late making lasagna. I was too tired to make bechamel, and I didn’t really know how, so I used ricotta. When we arrived at my mother’s the next day, two huge pans of lasagna in tow, my aunt and mom nodded approvingly.

“See?” My aunt said. “That’s not the sort of thing an American girl would do.” My mother agreed.

I smiled, not because it was true (I am as American as they come, for one thing), but because I knew this was high praise indeed. The only one who objected to my lasagna was my Uncle Enzo, who said that it “wasn’t bad.”

“But,” he added later, “you can tell an American made it.” This was a heavy insult. If his brother hadn’t just died, I might have killed my uncle for it.

Because in my family, we’re all competing for one thing: who is the most Italian.

I’m sure that similar dynamics exist in other families. Debates and conflicts are passed down from parent to child, sides taken simply because that’s the way it’s always been. Everyone competing for some crazy goal, the importance of which has escaped them now. We want it not necessarily for what it is – a particular spot on the couch, the center square of brownie, the last meatball in the pan – but because of what it means in our family: that we are, among our cousins and aunts and uncles and siblings, somehow special.

For us, it comes down to how Italian we are, though no one seems to admit it. The arguments take place, sporadic and non-sensical to an outsider. This holiday season, we had many of them. Nearly every year, my mother and aunt fight over which Christmas it was when it snowed in Rome.

“P,” my mom will say, her head held high, “I think I would know better than you. After all, I was born there.”

After that, my aunt will usually let my mother win. Nevermind that my aunt was born in Italy, too, but in my grandfather’s village. Certainly not in Rome. Not in the heart of all.

Or how my cousin Massimo will quietly sip espresso, reading the pink Italian sports newspaper, La Gazzetta dello Sport in the mornings, and my cousin Marco will marvel at it.

“He’s more Italian than I am,” Marco will say, laughing quietly to himself. And it some respects, it’s true, even though Massimo came to the states decades ago, and Marco only just moved here.

And, of course, there’s the al dente-ness of the pasta we make. When I was down in California a few weeks ago, I made my aunt pasta twice (using her sauce. I wouldn’t dare serve her my own), and both times, I cooked it to a perfect degree – chewy with just a bit of give. Even Auntie P. noticed.

“This pasta,” she said, looking at me proudly, “is perfectly cooked.”

There are times when it isn’t perfectly cooked, and in my family, that’s usually because we’re trying to out-do one another, as always, with how raw of a noodle we will eat. I’ve bitten into my mother’s penne to reveal the brittle white insides, never permeated by water. Or Massimo’s pasta, which once was so crunchy I swear I cut my cheek, but which my mother described as “perfect.” Just a few weeks ago, he made a pot of pasta which my mother deemed perfectly cooked, and Massimo quietly said to no one in particular, “I like it a bit more raw.”

And of course, there came the compliment of all compliments for me – when one of my cousins, describing my husband, said, “He’s not American. He might be born here, but he’s Italian.”

I don’t think he was trying to make the point that Americans are bad. Instead, I think he was trying to say, “Rand is one of us. He’s part of the family. He’s Italian.”

Maybe, in our case, this strange competition has something to do with so many of us being immigrants. If you can’t fit in, you hold on to the things that make you stand out. Since we weren’t quintessentially American, we embraced being Italian. It gives us a hold to the past, to things and people we’ve lost. To the one man who was more Italian than any of us, more Italian than anyone I’ve ever known.

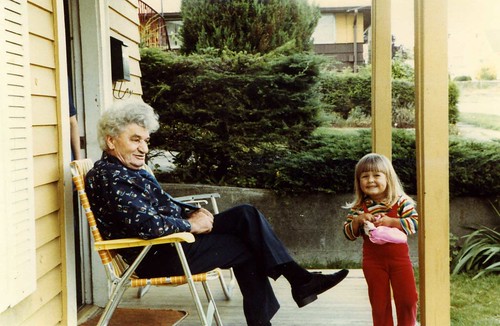

The Everywhereist with her grandfather, circa 1983.

–

And, rather unexpectedly, it ties us to the future, too.

My cousin's kid, eating pasta. If he's anything like his dad, these noodles are overdone.

Leave a Comment