This Holiday Season, Be A Selfish Cook.

Despite my numerous protestations, several letters to the editor, and one shockingly well-funded Kickstarter, Thanksgiving is somehow upon us again. If you are anything like me (clinically depressed and awesome), you are wondering how we ended up here again. In my case, I assume it’s punishment for the time I said Vince Vaughn was “kind of bangable” in the early 2000s.

For the record, I don’t hate the holidays (though societally, we have entire airplane hangar of shit to unpack around Thanksgiving). I don’t even hate cooking for the holidays. But I hate the way that gender roles around cooking and hosting become more entrenched sometime around November 10th, and don’t let up until mid-January, or, for some people, ever.

In 2022, I wrote about how it’s okay to buy pumpkin pie (it is! If you want to! It’s an incredibly easy shortcut and honestly there has never been a homemade pumpkin pie that is demonstrably better than a store bought pumpkin pie, THIS IS FACT) and while a lot of people agreed with me, a small mob of folks armed themselves with dessert forks and brûlée torches and called for my head on a platter.

One culinary celebrity snapped, “Making it from the scratch is the point,” and in doing so, missed mine entirely. I wasn’t saying that he couldn’t make a damn pie. I was saying that in a world where the task of cooking and feeding our families falls disproportionately to women, and this disparity becomes even worse during the holidays IT IS OKAY TO MAYBE GIVE YOURSELF PERMISSION TO BUY A FUCKING PIE BECAUSE SOME OF US ARE BURNT OUT. Among American heterosexual couples, women do more meal prep, cooking, and cleaning than their male counterparts – something that holds true whether or not they have children. Worldwide, women cook twice as much as men do (with the exception of … Italy? Huh.). Praising store bought pie isn’t an indictment of those who make it from scratch. It’s just cutting some of us some fucking slack when we need it.

Last year I threw even more cinnamon on the fire and made a clear pumpkin pie as an allegory for the invisible labor women do around the holidays. 2 million Instagram views later, a handful of people were so filled with the spirit of the season they told me I needed to kill myself.

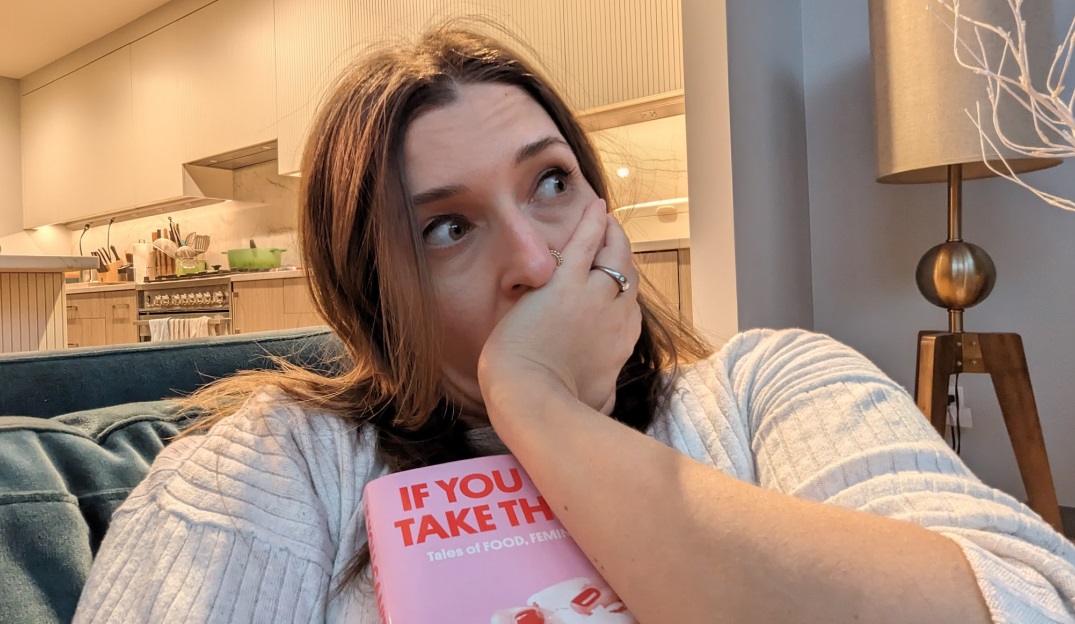

This year marks my first holiday season without my aunt. She died in February, in an act of mortality for which I have not yet forgiven her. Among the many things she taught me (including “Make sure to leave at least one survivor so they can tell the others what they saw here today”) is that there is joy in being an extremely selfish cook. Women are constantly expected to feed their families — either directly from their own tits or from their thankless efforts in the kitchen. It is exhausting and back-breaking and painful and even if it’s rewarding it’s still work and yet we’re told all of these very difficult things are a gift and an honor.

In light of that, I see my aunt’s particular brand of cooking for the revolutionary act it was.

To be clear: she was an aggressively hospitable host, feeding people via a mix of coercion, guilt, and brute force. I’ve never seen anyone look more personally affronted by the phrase “We’ve already eaten.” She would gladly cook for you, but it was invariably whatever she loved eating.

My aunt wanted things done a particular way: hers, and no one else’s. Because her way was better than yours. Her way was the best way. And if you disagreed with her, you were wrong. She was quick to inform you of this. Often several times a day.

She would slice up jalapenos and chili peppers and keep them in a jar under oil, the entire concoction so spicy that you simply needed to drizzle a few drops a little over your food to burn off a layer of your tongue. (If I were to go spelunking in the recesses of her fridge, I am certain I would find jars of them, still. Her cooking outlasted her, which I suppose isn’t surprising). She preferred pecorino on pasta, so that’s what she had in the house (never parmigiano). Her garlic bread was blackened with a thick layer of pepper on the top because “otherwise it doesn’t taste like anything.” Her banana bread was dry and crumbly, the texture and color of stale cornbread, palatable only with a thick layer of butter on top and a cup of her milky tea. Her apple pie had entire studs of cloves nestled inside (as a child I would often fish one out of my mouth, an unpleasant little discovery that in no way stopped me from eating more pie).

The important thing was this: she liked things this way, and the gods and Julia Child could not sway her otherwise. Cooking was never a chore for her, was never something she resented, because at the heart of it, she was always doing something for herself. She was her own personal chef, her own short-order cook. She fed me ten thousand times and I don’t think she ever asked me what I wanted to eat. It was just “You want some pasta?” or “Shall we make some gnocchi?”

She wasn’t going to relinquish the power of deciding what she was going to make, not even to those she loved. This is counter to so many things that I’d seen and read. As women, it wasn’t enough for us to simply cook for others – there needed to be something self-sacrificial involved as well. We had to be denying ourselves something, because a woman who enjoyed her own cooking, who catered to her own tastes was just … unseemly. There had to be a dose of martyrdom thrown in. Leave out the spices we enjoy, omit additions we loved, soften the sharp flavors of both a dish and ourselves.

What we don’t talk about is that if a dish is palatable to everyone, it is inherently a little bland.

And so while my aunt was happy to cook for others, she did not cook for others’ tastes. She was making her food, the way she wanted it (she just happened to make enough to share). When she was too ill to prepare food, she would dictate how something needed to be prepared from her cushioned chair in the dining room, a culinary grand dame. On occasion, I was the recipient of her orders. In those instances, I would shout back, “Zi, I’m doing it my way.”

This would leave her in a sort of stunned silence. For a woman with such a formidable palate, you’d think she would have been less affronted by a taste of her own medicine. But I was simply doing exactly what she had taught me to do. I was transforming that kitchen – a setting of confounding contradiction, our near-exclusive domain and where we were expected to spend so many uncredited hours – into a place of pure, unadulterated, glorious selfishness.

This holiday season, I recommend that you do the same.

If you are compelled to cook, take your own tastes into account. Make dishes you love, the way you love them. So many of us have been taught that to put ourselves first, or at least on par with everyone else, is to be selfish. And that’s wrong, but even if wasn’t – so fucking what? Let’s be selfish. Let’s cater to ourselves. Because when I reflect on the many lessons my aunt taught me, one that stands out is this: that when we talk about cooking for our loved ones, we should have been including ourselves in that equation.