When Online Harassment Shows Up on Your Doorstep

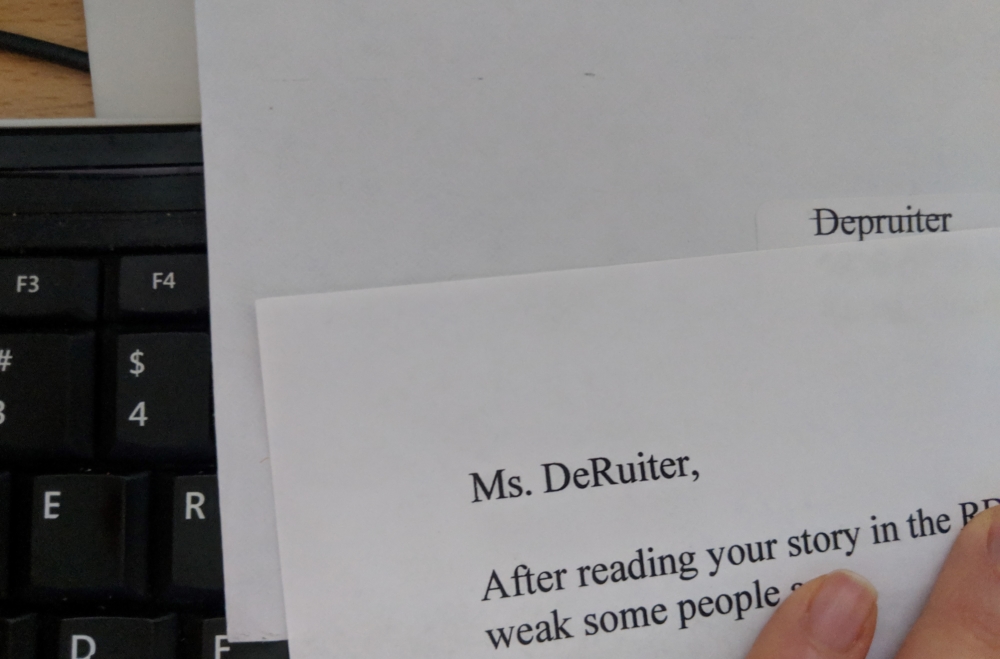

The letter arrived at my house at the end of October in a plain white envelope with no return address. My name – or some approximation of it (“Depruiter” it reads, because, in the words of my beloved, “The person who addressed it is an idiot”) has been printed out on a label and affixed to the front. The nondescript nature of it set off some sort of alarm in the back of my brain – something wasn’t quite right, though I couldn’t say what.

We get a lot of mail. I’ve tried to whittle it down as best I can, but towards the end of the calendar year there’s always uptick in it. I rummage through countless catalogs and requests for donations from specious sounding not-exactly-non-profits to pick out the things I want to keep – primarily a handful of holiday cards that I will display on our mantle until they’ve collected dust in February or -who am I kidding?- April.

I suppose for a brief moment I figured the card was the latter – someone had printed out an annual family newsletter and skipped a fancy envelope and return address. “Depruiter” in that context, wasn’t all that surprising – some of my own family members can’t spell my last name.

I torn into the envelope, and found my name spelled properly on the inside.

“Ms. DeRuiter,

After reading your story (on bullying) it never ceases to amaze me how weak some people are.”

The writer was referring to an article I wrote for The Washington Post earlier this year – a piece about having more empathy for bullies, and how I felt when I found out my own childhood bully had been murdered. How I grieved for the little boy who’d made my life hell.

I read on. The nature of the first sentence could have been taken either way – perhaps the writer was referring to my bully in that first sentence – perhaps he was misidentifying one child’s manifestation of pain as a weakness (and completely missed the point of my article in the process). But it soon became clear that he was talking about me. I was a victim of bullying because I was weak.

The rest of the letter included a shockingly graphic story of violence – one which he inflicted on his bully, ending his antagonist’s luminous high school football career (which sounded like a disproportionally severe punishment for the sort of antagonism that the bully inflicted, even by the victim’s own account). He rambled, incoherently at times, lauding his own career in the Air Force (from which he’d retired after 30 years).

“That’s how you deal with bullies,” he wrote at the end of his letter. There was no signature at the bottom, no name, nothing to indicate who’d written the garbled, violent nonsense that had appeared in my mailbox.

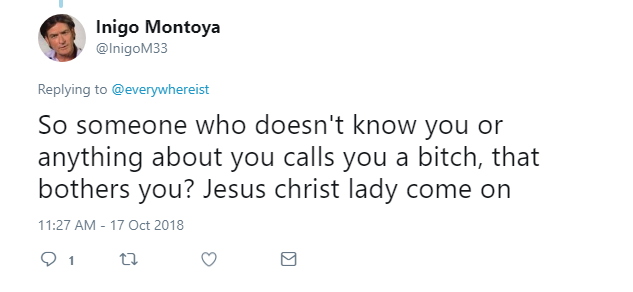

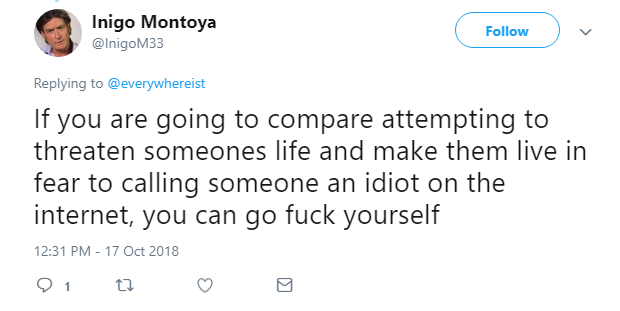

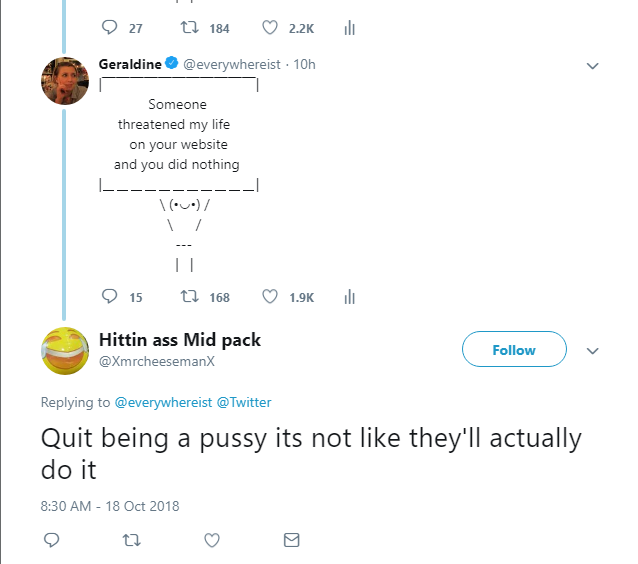

Those of you who follow the blog know that I get hate mail. And hate tweets. And hate comments. And hate Amazon reviews (which are rarer because they usually require a higher level of literacy and a credit card). If there is an anonymous medium in which to convey hate, I’ve received it. Some days, if there is more fight than judgement left in me, I will reply. I will ridicule them for their undoubtedly terrible grammar and awful punctuation. But more often than not, I delete and block. If a threat is incredibly egregious, I’ll screencap it for reference before reporting the person to a site or platform moderator (an entirely Sisyphean effort which yields nothing other than a fleeting sense of hope). And then I try to go back to my life as a -*checks notes*- “vile, man-hating cunt.” (Which is a pretty great life!)

This letter, despite the description of graphic violence, wasn’t unusual. It was milder in nature than many others I’d received but no less anonymous. It was in response to a piece that was higher profile but not particularly controversial – most of the replies I’d received for the article had been incredibly, effusively supportive and thoughtful. A lot of people told me that they’d started looking at their own childhood bullies differently. The entire experience of writing for the Post had been a positive one from the editing process down to most of the replies the article received. But this damn letter shook me to my core for one very significant reason.

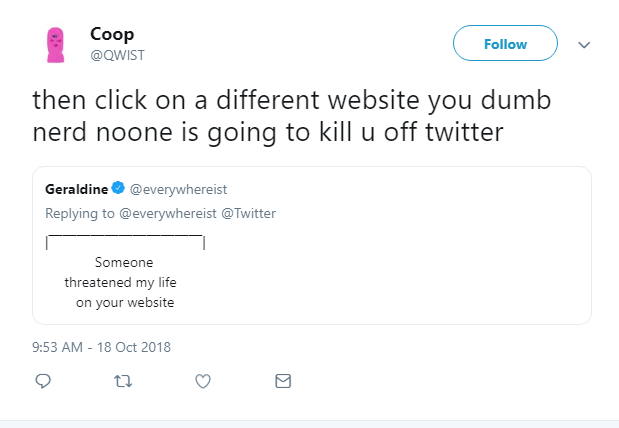

The person who wrote it had sent it to my house.

After it arrived, I frantically searched online for any websites that had my address listed. Past threats mean that I’ve already done this, and requested it removed from numerous listing sites, but one or two had failed to honor the request. I sent them scathing follow-ups. A friend of mine who has dealt with extreme online harassment (doxxing, death and rape threats, stalking) told me that it’s largely a futile effort. My address is out there. So is yours, probably.

Being a woman with an online profile has strange ramifications. The barrage of harassment is so consistent, you start to forget what’s a reasonable reaction to something and what isn’t. We are told repeatedly that online harassment is simply words – an argument that ignores the fact that verbal abuse is abuse. Being called a cunt, being called stupid, or weak, or threatened with graphic accounts of rape or violence is no less terrifying because it’s being meted out to us 240 characters at a time.

We are told that the threats we receive are nothing to be concerned about – that they remain online, as though somehow there’s a line of demarcation between the internet and the rest of the world. (Spoiler: there isn’t. We do everything online. We buy plane tickets and clothing and groceries, we do work, we interact with friends and family, we watch TV shows and movies, we pay our bills and our taxes. The internet is real life. Those who pretend otherwise are simply trying to separate themselves from the consequences of their actions). That the horrible things that people say to us on the internet can never hurt us in real life.

That’s bullshit.

Besides just being psychologically taxing and stressful as hell, there are plenty of other real-world implications to online abuse. Astroturfing – concerted, fake, harmful reviews by hateful misogynists of female-fronted projects – can destroy careers. Doxxing can force victims from their own homes. The threats which begin online can be so intense that conferences stop inviting certain speakers because the security risk is too great.

And sometimes the bullshit that happens to you on the internet shows up at your doorstep.

When writer Jill Filipovic was in law school, she found hundreds of threads about her on an anonymous online platform designed for students at her university. The comments were a litany of graphic, sexual threats (“I want to brutally rape that Jill slut,” “I’m 98% sure that she should be raped,” “that nose ring is fucking money, rape her immediately”). She notes that what truly shook her was when one commenter said that they’d met her, and that she was extremely pretty in person. The comment wasn’t graphically violent – it was even kind. But for Filipovic, it broke down that barrier between the online and the so-called real world that so many of us pretend exists.

What followed was numerous people – in an online thread about how she deserved to be raped – chiming in about the times they’d met her in real life. The implications of that are terrifying.

“Well, they aren’t going to show up on your doorstep and do that in real life,” is the oft-heard refrain I hear from those who say that I take online abuse too seriously.

The onus on solving online abuse is placed on the victim – not on the person making the threats, not on the platform that enables it or the online culture that fosters it. The problem is that we, supposedly, need to toughen up. And so many of us have. I’ve seen how people change – how I’ve changed – from the constant barrage of insults and threats. You become a different version of yourself. You become hardened and numb. But that doesn’t address the problem. Being numb to rape threats isn’t a superpower.

Not-so-fun-fact: You can’t actually turn online harassment off. Even if you walk away from your computer, it stays with you.

And it doesn’t stop the harassment.

(None of this is new information, I realize. But it seems like until something changes, the only alternative is to repeat it until someone in power listens.)

After Filipovic graduated, one of the men from her forum showed up at her office hours, incoherently yelling at her about things that had appeared on the forum. She would later find out that he was in the middle of a psychotic break, one that he would later be hospitalized for. She managed to get out of the situation physically unharmed (and he would later be arrested for making death threats … to someone else). But the barrier between the online world and the offline one was forever broken for her.

The letter I received from the anonymous, ranting assaulter is nothing close to that terrifying. But it sits on my desk, and though there is no way I should be able to find it amidst the pile of papers and receipts that make up my workspace, I know exactly where it is. My hands go to it instantly – under a pile of paid bills I have yet to shred – drawn to it like a homing beacon. It makes me anxious, but I feel like if I throw it out or tear it up, I’ll unleash something worse – like I’ll somehow become possessed with the soul of an angry old misogynist and start screaming that the wage gap is a myth. At the very least, I’ll have destroyed the evidence. And that seems like a bad idea. So instead it just sits there.

I can turn off my computer. I can stop tweeting. I can stop working in a field that I’ve invested so much time and energy in. I can give up my career. It’s unfair to ask me to do any of those things – and besides, even if I did, it wouldn’t matter. Somewhere, that guy, and thousands of others like him exist. Odds are, he won’t do anything. But he still knows where I live. You can tell me that the harassment that happens online stays there. But this letter on my desk tells a different story.