The Alhambra, Granada, Spain

I’m going to tell you right now: when I visited the Alhambra, I took a lot of photos.

View from the Generalife Gardens at the Alhambra.

Like, a whole lot of them.

There is this weird travel mentality I’ve heard about now and again – that certain things are too great to capture in photograph form, and that you shouldn’t even endeavor to try. Anthony Bourdain, the tattooed patron saint of travel writers, said that he stopped snapping photos when he first visited Angkor Wat because he knew he could not do it justice.

My beloved, showing due reverence.

And my response to that is always the same, “Bourdain, you have an extensive camera crew with you, so stop acting like your refusal to take selfies makes you better than me. YOUR WHOLE LIFE IS A SELFIE. Now quit yapping and make me some steak frites.”

Also: obligatory selfie.

I’ll even grant that there might be some truth to the sentiment – sometimes photos just aren’t enough. But I’m still going to try my damnedest. I’m going to take a thousand blurry images that don’t nearly capture the immensity of a place, and hope that maybe, maybe you’ll get some small inkling of how remarkable it all is because honestly words just don’t cut it.

Marveling at the architecture.

That’s what I did at the Alhambra. Half of the time, I buried my face into my camera, because it was one of the few ways I could actually process the place. Otherwise, it’s just too much. Otherwise, I feared it might break my already-overtaxed brain.

Our friend Ethan recommended the place to us. An avid traveler, he said it was his favorite place on earth, and that we’d need to make reservations well ahead of time (Rand booked our tickets three months beforehand). While jaunting around Spain with Rob and Clayton, we made a point of stopping in Granada for a few days expressly for visiting the palace.

Just jaunting around Spain with three absurdly handsome men because that is my life. SUCK IT, ANTHONY BOURDAIN.

The Alhabra began as a small fortress in 889 AD on the remains of some ancient Roman structures (note: when studying European history, just assume that the Romans were everywhere, because they basically were. They were like Nick Cage, and Europe was basically every action movie of the 1990s). It’s on a gorgeous piece of real estate – a high, mountainous location with sweeping views that made it a strategic military site, but was mostly used as an estate for emirs and sultans. A Moorish palace was constructed there in the 13th and 14th centuries (Moors had been in Spain since 711 AD – their influence in some of the architecture and artwork Spain are still evident) and the Alhambra served as a palace to generation after generation of Islamic rulers.

Here it is from a distance, during the day:

And here it is at night, looking all brooding and mysterious like that goth kid in AP history class you sort of had a crush on.

The gardens surrounding it – known as the Generalife – are verdant and lush, especially given their rocky surroundings. They are some of the oldest known Moorish gardens still in existence.

Under Moorish rule, other religions were allowed, but at a price – the Christian and Jewish regions within Spain had to pay taxes to maintain their religious freedom. But all three managed to coexist (rather peacefully, for a time) and artisans from all three of these major religions played a part in creating the Alhambra.

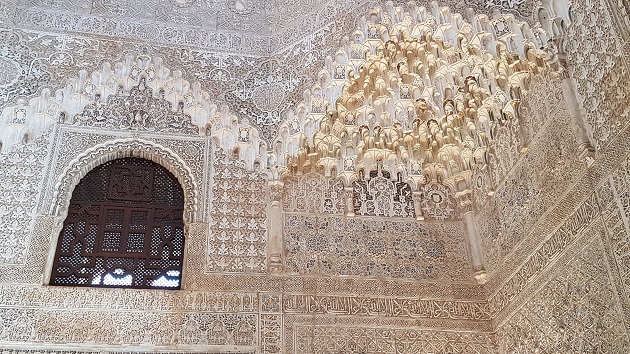

There are vast halls filled with intricate carvings.

They stretch all the way up to the ceiling.

Some are decorated with muqarnas – a sort of carved, ornamental vaulting that hangs down like gorgeous geometric stalactites. Someone explained that the pieces are carved in clusters which are then pieced together, supposedly without glue or adhesive. They just fit together like puzzle pieces.

At one time in history the entire palace was brilliantly painted, and while most of this has faded over the years there are a few spots where you can still see hints of color.

The reds and yellows are gone, but traces of blue and green paint still remain.

Imagine that the carvings depicted in the above are, more or less, life size. The width of one of the carved arches is, say, 2 inches or so. Now imagine an entire room massive room like that. And keep in mind, it was once entirely painted in a variety of colors.

It’s beautiful and overwhelming.

(Life with this guy usually is.)

During the Reconquista, Christian military forces began reclaiming parts of Spain, and didn’t return the favor of allowing other religions to exist (even at a price). Virtually the entire population of Jews were ousted in 1492. Muslims were either forced to convert or were expelled from the country. For a while, Granada was able to pay taxes to maintain some level of autonomy and religious freedom, but in 1492 it became the last Islamic state in Spain to fall. In that year, the Alhambra became the site of the Royal Palace of Ferdinand and Isabella and it was there that Columbus received royal endorsement to chart a new path across the Atlantic.

The Alhambra, which had been constructed over the reign of several sultans, didn’t do so well after falling under Christian rule. The palace a bastion of Islamic artistry: there were large chambers decorated in elaborately carved plaster and delicate mosaics, opening up into sunlit courtyards.

But after the Inquisition and Reconquista, Christian rulers destroyed huge portions of the original handwork, filled in pools, and boarded up arcades. Rooms were torn apart, partitions were put up, and a series of “renovations” gutted the once beautiful structure. Over the centuries it fell into ruin and disrepair, until a few enterprising architects (in the 1830s) began to restore the building under the endowment of the king.

And what’s left, while clearly not indicative of its former glory, is pretty miraculous nonetheless.

Do my photos do the Alhambra justice? Well, no. But there’s no way they could have. Some things are too immense, too lovely, too sprawling. You point your lens, you hope to get a piece of it that you can take home with you. It doesn’t always work.

But you can’t blame a girl for trying.