The Shoreditch Street Art Tour Changed How I See London.

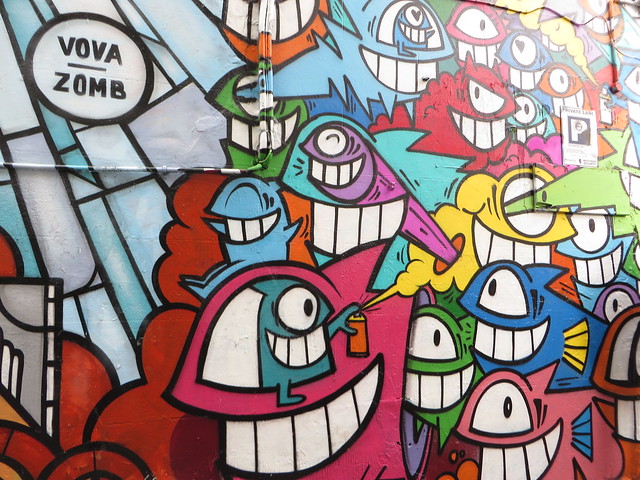

Detail of a mural that was painted with permission, by Vova Zomb.

Have you ever spent gobs of time with someone, to the point where you think you know everything about them, but then something happens and you start to see them differently? Like, after a dozen years together, you learn that they can touch their nose with their tongue (which, you maintain, is information that you really should have had much sooner)? But now that you know about it things will never ever be the same again, and it’s wonderful. (I would caution you not to read too far into that statement, but you know what? Go right ahead. Life is short, and my husband is a fantastic kisser.)

That happened on our trip to London last week. The city unveiled a long-hidden talent, one that was right under my nose, sometimes literally. And now everything is different. I learned that the streets are an art gallery; they are filled with paintings and collages and sculptures, waiting to be appreciated. I just hadn’t learned how to spot them yet.

Thankfully, David was able to teach us.

He was our guide on our tour of the street art of London’s East End. There were dozens of options to chose from, but David’s came well recommended and reasonably priced (£15 per person), and unlike so many tour operators, he actually replied to his email. So on a grey Saturday morning, we met him under the goat statue in Spitalfields. If only all paradigm shifts could begin thusly.

Our tour was slated to last three hours. Rand and I know ourselves well – we realized that hunger and jet lag would likely pull us away long before it ended. David had an utter lack of urgency about him – he was reserved and calm, leisurely strolling through London’s East End, and not inclined to economy of word choice; a dark-eyed Samuel Beckett waxing poetically about the art of the streets. The tour would not end early, yet we stayed until the very end.

It began here, on a street pole enrobed in stickers. I’d passed ones like it countless times before. I’d always regarded the stickers as litter – vandalism for weak-willed or non-committal types. David explained that each label was in fact a calling card for a street artist. They put their stickers up to let people know that this was where they were active; these streets were their canvas.

You’ve probably seen the image on the middle sticker before – it’s the work of Shepard Fairey, arguably one of the most famous artists in his field. He’s been active for nearly 30 years – his work can be seen in major museums (including the MoMA and The Smithsonian), and he created the “Hope” poster than became prevalent in Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign. But the image of André the Giant shown above was his starting point – he would use it in a widespread street art campaign early in his career, and a stylized version of it would become a recurring motif in his Obey clothing line.

We listened intently as David gave us a history lesson on the rise of street art. He talked about the conflict between artists and local police, the relationships between the artists themselves, and explained the difference between graffiti and street art. I am a dilettante, so forgive me if I botch this, but what I was able to glean was this: graffiti is a stylized mark, a sort of calligraphy that is meticulously crafted, and rendered in spray paint throughout a city. The location of a tag (which can be found anywhere from highway overpasses to train cars) serves to heighten an artist’s status and legitimacy, particularly when placed in hard to reach or precarious spots. David explained that we were not the audience that the graffiti artists cared about – their work was for each other, and not us.

In this respect, street art differs greatly. Passersby, though often oblivious, are the intended audience. They can interact with a piece, as David did when he delicately touched a painting by Alo, whose work is shown below. I found myself wincing before realizing that this was entirely acceptable. The overwhelming temptation to reach over and touch a work – the one that I feel whenever I’m in a museum – could finally be indulged.

That’s the point of street art. You can interact with it. You can touch it, or photograph it, or even destroy it. It erodes with the elements, it is washed away, it is built upon by other artists. It often becomes collaborative, like this piece:

We would see the one-eyed character in the middle – a hallmark of the artist Noriaki – numerous times throughout the city. Here it is shown emerging from a pasted paper piece by Endless.

David explained some of the unique characteristics of street art, like the running droplets of paint shown in this piece by Conor Harrington.

He told us the message that these running streaks carried with them – that the artist had no time to let the piece dry, that he was working under pressure, or perhaps the fear of getting caught. These streaks are present even in Harrington’s studio work; he often borrows stylistically from the old masters, but the runny paint reminds us that he is and will always be a street artist.

We listened as David discussed the many techniques used – the effect of layering stencils, of using wallpaper paste to put up collages, of sculptures adhered to buildings with glue.

Amazingly, this piece was created with a series of stencils, layered one atop the other.

The James Dean at center was done by Stikki Peaches (it was, I should note, positively delightful to hear David name each of these artists).

A collage by Sell Out, featuring the Kellogg’s cornflakes rooster, referencing vandalism that happened to a local cafe during an anti-gentrification protest.

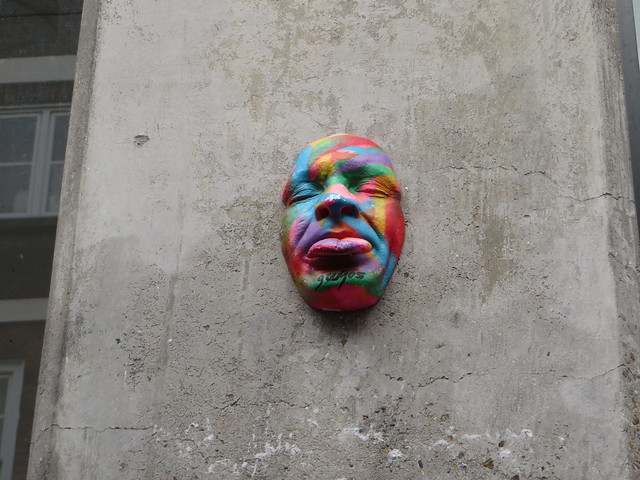

A sculpture by Gregos – a painted cast of the artist’s face.

Their was fondness in his voice; he spoke of the works like a docent describing favorite pieces in a museum. There was no pretension in his delivery; he was sincerely passionate about these creations, genuinely reverential of the artists who had made them. You could see it in how his eyes twinkled when he talked.

He overlooked nothing.

When street artists work with permission from building owners, rather than illicitly, they are able to take their time. Their tools can be placed on the sidewalk rather than kept in a bag (which makes for an easy getaway) – there’s no need to rush or flee, to hide behind the anonymity of a dark hoodie.

These works tend to be larger and more elaborate.

An incredible piece by Mr Cenz that was done with permission over the course of 6 or 7 hours.

Another piece by Mr Cenz, who describes himself as a graffiti artist.

A mural by Fanakapan, which is reminiscent of the work of Jeff Koons.

This piece by Jimmy C was one of my favorites. It’s a portrait of the owner of the adjacent coffee shop and her grandfather, based on a photo of the two of them which sits in the shop’s window. David explained that it’s rare that a piece relates so personally to the structures or people around it. I found it all incredibly sweet.

Towards the end of the tour, we encountered some mushrooms by Christiaan Nagel. Like their real-life fungal counterparts, they pop up all over the city, in the most unexpected of places.

Spot the mushroom!

Rather fittingly, we ended our outing with two pieces by Banksy, an old master in this relatively new field. Before the tour, he was literally the only street artist I could name. Now I realized he was simply one in a vibrant and prolific cadre of creators.

After a dozen trips to London I thought it held no more secrets for me, but now I found it forever changed. I realized the art of that old, bustling city couldn’t be constrained by the walls of its many museums and galleries. It spilled out onto winding streets and dark underpasses, into alleys and up the sides of buildings, like vines clinging to wall. It had all been illuminated for us and once revealed, we couldn’t unsee it.

This shift in perception followed us home. Walking through downtown Seattle, Rand pointed to the stickers on the pole of a streetlight, reading out the names of artists, admiring one piece that had been drawn by hand. I was in a city I knew better than any other, looking at it for the first time again.

One tour. Three hours. And now everything looked different, and things would never ever be the same.

—————

Here’s more info on Shoreditch Street Art Tours. As always, I received no compensation for my post, and I paid the full price of the ticket, because if I’m not willing to spend money on it, why should I expect anyone else to? I think it was well worth it.