It’s The End Of the Bird As We Know It: Thoughts on the End of Twitter

Last week, Twitter … did something. I don’t actually know the machinations of it, to be honest, and I’m at the point where I’m a little too fatigued to care. I heard whispers of something amiss. That Google could no longer crawl the site; that people were getting notifications that they’d exceeded their daily recommended allocation of tweets, a limit which never existed before. This time, I didn’t even bother logging in to check what the problem was. In recent months, it’s felt like a problematic teen that I’ve struggled to coparent with several million other people; I, finally, had had enough. Let it do what it wants. It’s going to end up dead in a ditch if it keeps up like this.

I’ve announced the end before, time and again, when he took over, when I lost my verified status, when my mentions started to once again fill with hateful vitriol and bot accounts because everyone who oversaw user safety had been fired. I said my good-byes, and slowly made my way to other social media platforms which promised to be better versions of it, but I kept wandering back. Afraid to leave out of the fear that when I did, things would never be quite the same again. But that fear ignored a simple truth: that the site has already changed, that so many of the people I loved had already left, that the safeguards put into place to protect us were long gone. The party’s over. Unwilling to leave gracefully, like so many others have, I’m waiting to be kicked out.

It is, of course, insufferably self-indulgent to eulogize the inanimate. To do so is purely a reflection of our own egos, of what the thing meant to us. But it’s impossible not to bask in ourselves, especially about a platform that demanded we do just that. Twitter has shaped my professional life for the last decade and a half. As a writer, it was the largest audience I had. The strength of the platform helped me sell not one but two books, both of which went to auction. I got assignments writing for major publications after editors saw my tweets. Twitter was the reason I submitted my work for a James Beard Award, based on a message from Max Falkowitz (and further loving intimidation from my friend Naomi):

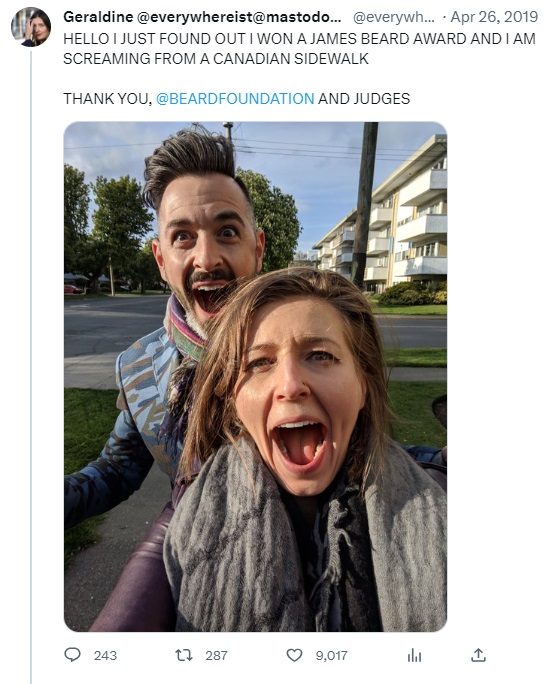

And it was there that I learned that I won, while standing on a sidewalk with Rand in Victoria, BC, slowly refreshing my feed on my phone. I’d been invited to the ceremony in New York. Convinced I didn’t have a chance, I decided not to make the trip all that way to simply find out I’d lost. I remembered what my friend Laura (who, along with many dear friends, entered my life via Twitter) told me: if you win, you won’t care where you are. (She was right, of course.)

This wasn’t unique to me – Twitter made it so that we misfit poets were able to have careers that once seemed impossible. We now had a platform on which to telegraph our work out to the world, to announce tour dates and gigs and speaking events and book launches and shows. The things we made had a chance to go viral, to be seen and shared by important people who might change our lives. Zoe Sandler, who eventually became my agent, found me because of an article I shared. My contacts at major publications first learned of my work by reading a post that went viral on Twitter. My second book proposal rested, in part, on articles that saw a much wider audience because of who retweeted them, on praise from luminaries in my field, parceled out 140 characters at a time.

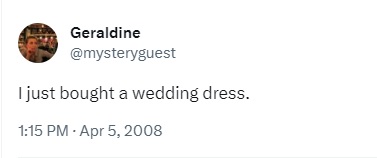

I first joined the site in 2007, pre-dating even this blog, under the handle of @mysteryguest. The platform then required users to send tweets via text, and I would type them out in T9 from my flip phone. Where photos were not embedded and quote tweets did not exist. That account still exists, filled with glimpses into my life as a 20-something that makes me feel as though a thread is winding itself around my heart again and again, drawing tighter. The feeling of longing for the young person I once was.

Mixed with this longing is the relief that comes from no longer being that person. That’s the monkey’s paw catch of all of it. Back then, all I wanted was the life I have now: the book deals, the bylines in major publications, the press engagements, and the travelling around with the love of my life. This is the dream. It’s here. I’m one of the luckiest people in the world, and Twitter played a crucial role. But when I look back through it, I find the fossils of my youth, the years when I was all potential. Here, from the other side of my accomplishments, I find myself wishing for that world, one full of uncertainty and newness, when everything was still in front of me. I feel like maybe I could have done more. Or done things differently.

26 to 43 is an immense journey; mine is charted on a single social media platform.

Twitter was not just a tool we used in our careers, but a scrapbook for our lives. My friend announced his son’s birth. I shared news of my brain tumor and impending surgery. I’ve seen engagements, and weddings, and funerals announced. Lives lived, in an endless stream. We shared news events, we celebrated and grieved together, we watched as the world slowly slipped into something ugly (or perhaps the ugliness was always there, and some of us were just becoming aware of it) and some of us tried to rally against it. And some of us just tweeted, and thought that was enough.

I am glossing over the bad. This is what we do in eulogies – we sugarcoat things. So I do not mention the time my account was hacked, or all the times I was targeted with a firehose of hate, or the guy who threatened to burn down my home; I seem to have a convenient, specific case of amnesia about the users who’ve doxed my friends, and sent the FBI to their doorsteps. The way Twitter became a breeding ground for Nazis and fascists, how horrible people convened and terrorized others off the platform. How it fueled my depression and anxiety and completely destroyed my productivity, so that the only times I ever wrote were on the platform, in a desperate plea for engagement. How in the weeks and months (and possibly years) after the 2016 election (which coincided rather brutally with my father’s death) I sat and stared at my phone for hours, unable to move. But I assumed, somehow, that goodness would win. Like any abusive relationship, I thought I could change it. I just needed to stay on Twitter, feeling awful and doing nothing else.

And in the end, I mistook it for living.

It’s hard to think about rebuilding, about going somewhere else, about having your career thrown into chaos when you’ve spent the last decade and a half amassing an audience on a platform you assumed would exist forever. My second book is coming out next year, easily the greatest accomplishment of my life, and I feel like I’m screaming into the darkness about it. I’ve started up accounts on mastodon, on Threads (I’M INCLUDING LINKS BECAUSE I HAVEN’T LEARNED ANYTHING), on whatever the next big thing will be (“Follow me on all of them!” I plead, along with everyone else). This is what we are supposed to do, this is how the internet has trained us. We have to compete to survive, if that’s how we’ve built our careers. Perhaps none of these sites will fill the Twitter void. And perhaps that’s for the best. Maybe it’s time to put the bird to rest. It was wonderful to us for a while, and it was also horrific, and it’s gone now, and we’re messed up about it, because that’s what grief is.

I remind myself that life was happening elsewhere; it always was. That even the friends I made on the platform are not there anymore, but are with me, real and wonderful and solid. The things we’ve built are bigger than the site. Twitter amplified my work, but I was still the one who created it, on this blog.

I come back here, to where it all began, and I get back to the thing I should have been doing all along. I write.