What is Left When We Go.

We went to Germany, and I cried.

Not right away. It wasn’t until the last day that I finally did. Rand asked if I wanted to rent a car to go down to see my father’s grave. He asked me in the early hours of the morning, when jet lag had us both exhausted but somehow wide awake, and rather than reply, I broke down. But it had been there all along, quietly simmering.

I cried until my nose was entirely clogged and I couldn’t breathe and Rand and I were almost laughing because it was just so, so much. It was the kind of sobbing that leaves you winded, like you’ve just ran to catch a train, the kind that makes your eyes well up even when you remember it later. Rand said nothing, and I couldn’t see his face, but he simply pulled me towards him in the dark and I soaked his chest with tears. I realized that I missed my father, broken as he was, and that I was so upset that I had nothing left of him, except, of course, as Rand continually reminds me, I do. I have so much left.

Even though my mother says, “You are so like him” and means it as decidedly not a compliment, I find something comforting in the idea.

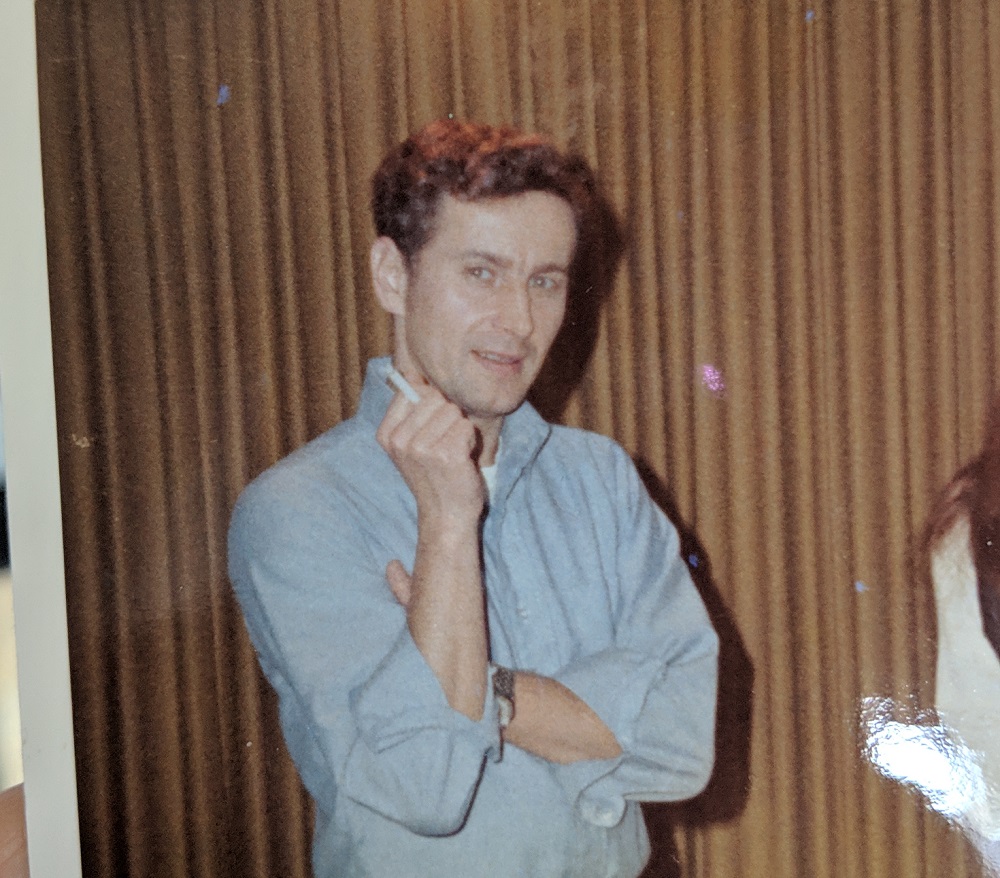

I’m so like him. But a lot less broken. Or maybe just broken in different ways. That is what remains, even now that his workshop is dismantled and his books and model planes are gone. The bend in my nose (as though it suddenly realized it was supposed to make a turn it forgot about), the tendency to scowl, the blue of my veins under too-thin skin. Sometimes when someone I love takes my picture, my instinct is to smirk and flip them off. I never knew why. And then it hit me that this was my father’s signature move. I hated when he did it. I hate it when I do it. But it comes out, like a reflex. Throw away everything he owned and reduce him to ash, and these things remain.

I showed someone a photo of my father when he was 11 or 12, and they noted that he looked much older.

“It was the war,” I explained. And perhaps that’s true. I can almost pinpoint the moment when my father stopped smiling, and he must have been around eight or 9 years old – just as the war was ending. Every now and then I’ll find an image of him with a half-grin, but that’s as far as it ever got. I suspect that’s the most he ever allowed himself. Even those rare times felt like an accident – like he was suddenly breaking character.

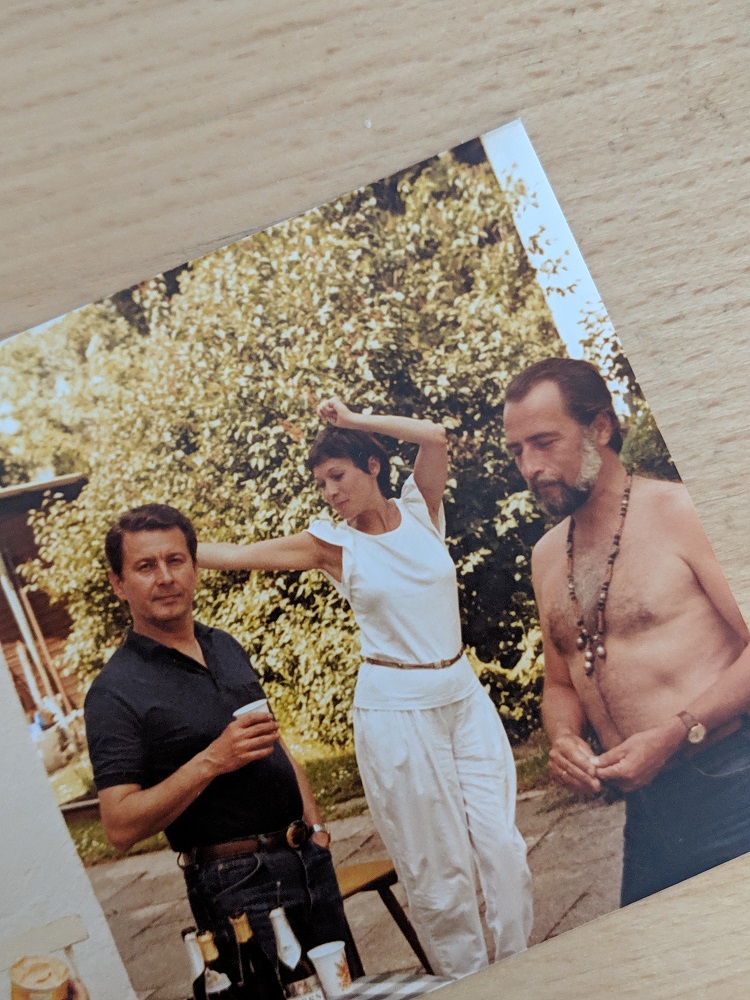

I love this photo because it is so on-brand for my father (left). The 70s were happening around him, but he simply did not care. His shirts remained tucked in, his hair remained short.

Those of us who knew him learned to read his face in other ways. We learned which of his expressions counted as a smile.

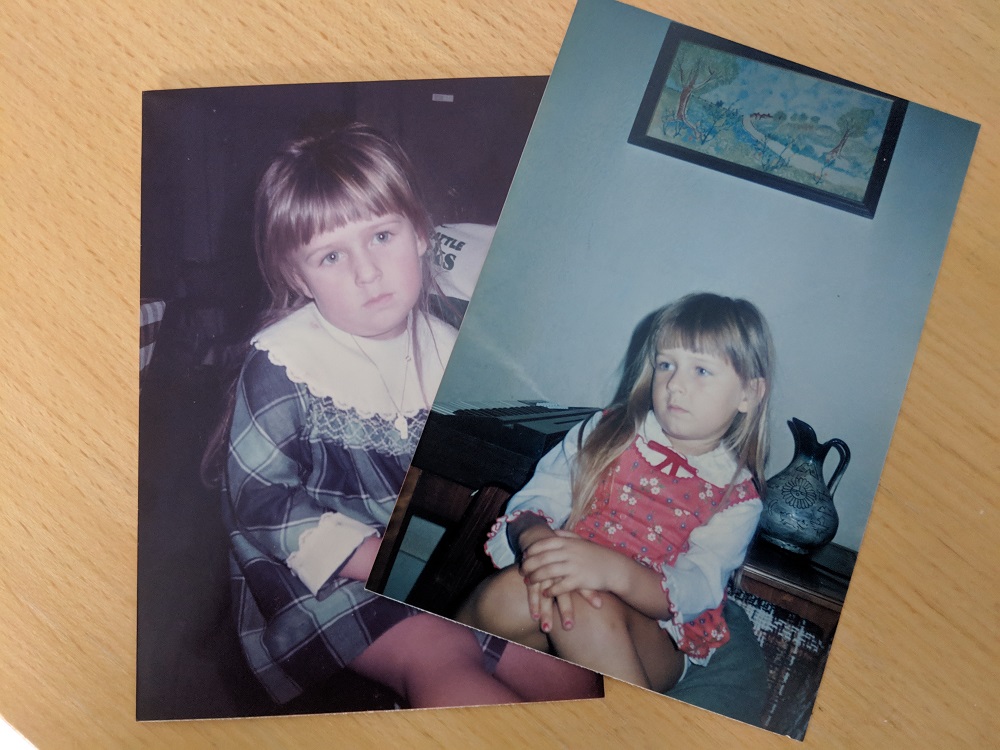

When I was small, I had the same problem – I could never get the hang of smiling. I remember strangers flashing wide grins at me in an effort to get me to reciprocate while I stared at them impassively.

I told Rand that I didn’t want to go to my father’s grave, or see the empty place where his workshop had been. It wasn’t that I wasn’t ready, but that I wasn’t sure what the point was. So instead I cried in the quiet of our hotel room in the middle of the night, feeling the tears roll down my face and into my ears and onto my husband’s arms and everywhere, just everywhere. I thought about all the things that I tried to hold on to after my father died, the things that slipped through my fingers. The memories of him, the pieces of his life that I couldn’t hold on to because distance between us – both geographical and emotional – wouldn’t let me.

Rand reminded me that these things weren’t important. That these things were just things, and having my father’s models or his cardigan or any of the letters I’d sent him over the decades of our relationship wouldn’t actually change anything. I simply think that they will because they are gone.

We are home now. Rand told me that we don’t have to go back to Germany any time soon, and I told him that I was okay with that. I look through the photos from the trip – the few that I took – and see my face, not smiling really, but still, not entirely not smiling, either.

And I about how when everything is gone, when everything is dead and buried, this is the thing that remains. My father’s eyes, staring back at me, and that same damn smirk.