Tragedy, Antisemitism, and Being Not Quite Jewish

I have yet to call my in-laws (my husband’s grandparents) in the wake of a shooting at a synagogue in Pittsburgh. A few days have passed. For the collective American consciousness, the lifespan of a mass shooting is short. The newscycle has already moved on, as has everyone’s social media posts. (Even this post, written two days ago, feels a little outdated. The timeline for caring about gun violence is too brief in our country. It’s like that by design.) The moment to reach out to my in-laws may already have passed. Perhaps I shouldn’t remind them of the tragedy. They are in their early 90s. Besides, I do not know what condolences to offer, other than that I am sorry and that I love them. I am unsure what else there is to say.

I will likely fish the hamsa that my aunt gave my mother years ago – a gift from her travels – out of my jewelry box. Most people don’t notice the charm when I wear it. Those who do are usually Jewish or Israeli. I nod as though I understand the meaning, as though it is more than just a reminder of my now-deceased aunt.

But wearing these icons and loving these people does not make me Jewish.

I was not raised in the faith, though one of my closest friends growing up (a woman I am still close to now, a woman I will likely be close to until the day I die) was. Through her I quietly absorbed her family’s religious traditions, watched as they lit candles, and ate matzo ball soup for the very first time in her home (her mother’s abject shock when she found out that I had never had it remains indelible in my mind. She immediately served me up a bowl, and digging into the spongy little orbs – a texture unlike anything I’d ever known before – I declared them magic).

But none of this made me Jewish.

My father was almost sent to the gulags as a child. The day before they were supposed to be carted off in trains, the Nazis took Kiev, and the Russia soldiers fled. I don’t know which battle of Kiev it was – there were two. But my father was either four or six at the time. In either case, the gulags would have been a death sentence.

And so instead he ended up in a displaced person’s camp in Germany. A step up from a concentration camp, the sort of place that you could survive even if you were an underweight kid. You’d get out with cavities in your teeth and a dark spot in your heart where your childhood should have been, but you’d get out.

My father told me about how a young Nazi soldier once shared a liverwurst sandwich with him. He said he had never tasted anything like it. And I realized that this was, for my father, one of the closest things he had to a happy childhood memory.

But none of this made us Jewish.

I’ve scrolled through my lineage, looking for it. There are scraps, here and there, a tiny sliver of Semitic ancestry. When I told my husband this, with some measure of excitement, he laughed. I married a Jewish man with kind eyes who is non-practicing and eats pork on a regular basis and forgets about the high holidays right up until they are almost over. He’s the first person in his family to marry someone who isn’t Jewish. The entire line stretches back, unbroken, with observers of the faith, right up until us.

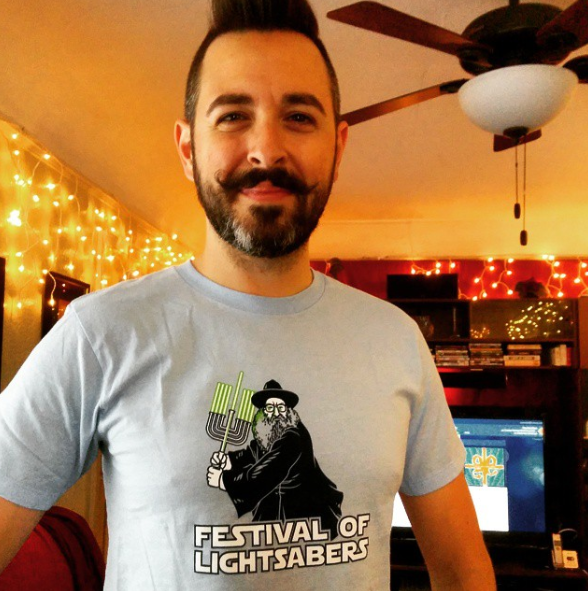

Rand during the holidays a few years ago, wearing his new Hanukkah present.

When a colleague of his called me a shiksa at a work event, Rand stared him dead in the eye and told him to never repeat those words again, before walking away. He’s refused to speak to him ever since.

When someone at a dinner we were invited to said that Rand didn’t look Jewish because he “didn’t even have a hook nose”, my husband gently placed his hand on my knee, ensuring that I wouldn’t leap across the table and stab him with my fork.

When I raged about it to my beloved later, he whispered gently, “I know.”

This was all new to me, but not to him.

Rand at Hanukkah a few years ago. He’s wearing a blanket draped over his shoulders, but it looks like a multi-color tallit.

I’ve been told the Holocaust never happened, and that Jews control the media and the banks and the government. Most people can’t tell if I am Jewish or not, so they simply assume that I am and lump me into the group. “You’ve done this,” they say. We each have been called the k-word. My husband has been threatened with the gas chamber. His maternal grandparents narrowly made it out of Europe during WWII as children.

That’s the patina of protection I get from having my Jewish ancestry be so far out. From knowing that the camp my father was in during WWII was one he could get out of. And so these comments don’t cut me as deeply as they could. They never can.

But they still cut.

Because though I’ve grown desensitized to the horrible things said about me, the horrible things said about the people I love still manage to hurt. And I don’t know if that is a good or a bad thing.

When news of the shooting broke, I checked on my husband’s cousins in Pittsburgh, to make sure they were safe. I wondered what I’d say to my grandparents-in-law. I hugged my husband.

I am not Jewish. I will never know the pain of this specific hate crime as acutely as those close to me do. But the line between the people we love and ourselves is a thin one. You do not need to be Jewish to be enraged by Antisemitism. And you do not need to be Jewish to be heartbroken.