I Watched All the Fast and the Furious Movies in A Week.

Over the last week, I have watched the entire Fast and the Furious series. The impetus for embarking on such an artistically dubious project was a promise that I made years ago to my husband, probably while drunk. I told him that the next time I was struck with the sort of mind-numbing illness that allows one to do little besides produce mucus, I would watch the entire series and write about it. I rarely get sick, my husband has a terrible memory, and at the time, there were only four films in the canon. I assumed I would never have to make good on my promise. I was wrong.

Up until this point in my life, the most significant thing that could be said of my relationship with the Fast and Furious oeuvre is that I had never seen them at all. In the 17 years since the first film came out, I felt no glimmer of temptation to watch any one of them; it wasn’t that cinematic snobbery kept me away, but that we existed in two different worlds. Mine is filled with cellulite and public transportation.

But the cold that plagued me for the last few weeks had sealed my fate. I lay on the couch, unable to move. I’d gone through all of The Good Place, This is Us, and Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. (For those wondering: I am a clearly an Eleanor; do not start watching if you haven’t; Team Nathaniel.) My husband knew this. My white blood cells were up, and my excuses were dwindling.

There are now eight films in the series. They were inescapable.

Everyone who learned of this project made it clear that the first four films were terrible, and that I would have to endure them as payoff for the fifth film. I would suffer through them as man suffers through life on earth for the reward of heaven, which in this case is Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson and a plot that felt positively Shakespearean by comparison. As promised, that fifth film would shine like a beacon for me. I cannot see it objectively. If you are dying of thirst, you do not complain if the water that saves your life is lukewarm. Fast 5 is a masterpiece, or perhaps it just marks the moment when I lost my mind.

The rest of the films blur together in a haze. There are moments that stand out (every time that Michelle Rodriguez genuinely smiles caused my heart rate to increase far more than any on-screen explosion) but seen in close proximity to one another, the plots, the car chases, the villains become almost interchangeable.

Let us try to sort through this cloud of explosions and hand-to-hand combat and tank-tops worn to formal events. Let us go back to where it all began. Every great story has a beginning, and The Fast and Furious also has one.

The first installment in the series came out in summer of 2001. This is America during that narrow epoch at the beginning of the millennium before the attacks on the World Trade Center; a simpler time, when an entire police force was able to devote seemingly infinite resources to figuring out who stole a bunch of TVs with built-in VCRs. My husband comments on how young Jordana Brewster looks in the first film, and I find that we are the same age. As the series progresses, she remains lovely, but her face loses the roundness of youth. I become acutely aware of my own mortality.

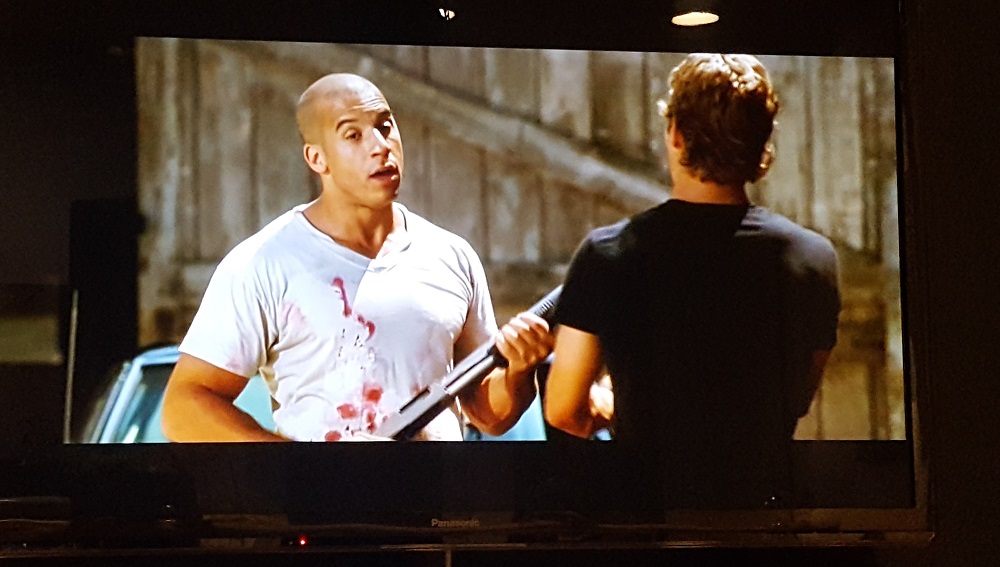

The plot is de rigueur for an action film – Brian O’Connor, a rule-bending cop (Paul Walker) goes undercover to infiltrate a gang of thieves by befriending their leader, Dom (played by Vin Diesel who growls through his performance with a sort of brutish charm). The lines between good and bad are obscured. So are the lines between “acting” and “staring blankly at something slightly off-camera.” Someone notes that it is Point Break with cars, but this comparison is unfair. A bad movie, if gloriously entertaining, has merit. Stupid and fun is fine. Stupid and boring is not.

The first entry in the FF canon leaves absolutely no need for a sequel. And yet there will be so many more. I have not the energy to describe them to you individually, and let’s be honest, dear friends: it doesn’t matter. Watch any of these films, hell, watch the trailer and tell someone that you’ve seen them all. In some sense, it will be true.

You may think, “Ah, but what if they ask me trivia questions about the films to prove whether or not I’ve seen it?”

At which point I must ask: Who is this person? Why are you hanging out with them? Do people often assess your value as a human based on your knowledge of action films? At any rate, should that happen, just offer them this – it is the ranking of the Fast and the Furious films in order from most tolerable to “oh god”

Five

Six

Four

Seven

Eight

Two

One

You will need to pepper the third film (which has a 37% rating on Rotten Tomatoes) somewhere near the end, for, dear friends, I must confess: we skipped it. It was only available for purchase and not for rent, and consequently far more expensive. Someone correctly ascertained that anyone actually willing to see Tokyo Drift will do so regardless of price. It’s the film equivalent of a condom in a minibar – the cost, in the end, is irrelevant. I later learn that supposedly the events of Tokyo Drift were to have occurred after the sixth film in the series. Like physics and gravity, time is meaningless in the Fast and Furious franchise.

“What if the real Tokyo Drift was in our hearts all along?” I whisper to my husband.

“That doesn’t even make any sense,” he says.

This will not stop me from repeating this refrain no less than 30 times over the course of the week.

It is cold outside – this February is particularly bitter in Seattle, but on our television is a world of endless summer. The Furious universe is not small – it begins in L.A., moves to Miami, then across the world, to the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Spain, Monaco, Brazil, Cuba, Japan – almost always in sun-drenched climes. (There is a brief jaunt to Russia, but the main purpose of this, from a plot perspective, appears to be “DUDE WHAT IF WE PUT A LAMBORGHINI ON ICE”). There are miles of roadway and expanses of taught bronze skin. These are easy distractions when the films don’t make sense, which is often.

As we work our way through the series, the humble street racers of the first few films will become the world’s most capable freelance counter-terrorism unit in a transition that is both imperceptible and instantaneous. Ludacris (who is, without hyperbole or sarcasm, absolutely delightful in this series) somehow makes the leap from garage owner/amateur bookie to one of the world’s best hackers. Tyrese Gibson goes from embittered con to jester in zero easy steps. Being able to drive a car also means being able to ride on top of one with ease. Everyone is suddenly expertly skilled at hand-to-hand combat and also parkour. They also all have six pack abs. Seeing their very human beginnings, there is something inspirational about where they end up – perhaps we are all destined for greatness. We just don’t have the right script.

When a film presents a protagonist with super human powers, we accept it handedly. Such is the magic of film. The FF series reinvents their characters half-way through from mechanics and racers and criminals to quasi-superheroes – yes, this stretches our suspension of disbelief – but does it do so significantly more than anything else? We’ve already been asked to abandon all notions of reality, of plot structure, of gravity. Why do law enforcement agencies keep hiring Paul Walker’s character, even though he keeps committing like, a whole bunch of crimes? Why does Jordana Brewster’s Mia, who seems like a reasonable, intelligent, tough woman, make such wildly bad life choices? Why would you surrender to police on the grounds that you are “tired of running” and then IMMEDIATELY BREAK OUT OF PRISON? WHY WOULD THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT THINK THE RIGHT MAN FOR THE JOB IS A GUY WHO IS REALLY GOOD AT DRIVING FAST CARS AND HAS LITERALLY NO OTHER CREDENTIALS?

To fully appreciate the canon, these questions must go unanswered. We must practice acceptance and forgiveness and a prevailing disregard for continuity. A villain who murders a beloved protagonist will suddenly be invited to family dinner. (Ancillary drinking game: take a shot every time Vin Diesel refers to his group of vigilante race car drivers – some of whom he barely knows – as “family”. You will have cirrhosis immediately.) Cops become criminals. Criminals become heroes.

A character who dies in one film will be resurrected in another. And an actor who dies during the filming of one movie will live on forever and ever.

Walker, who was the heart of the franchise, starring in every film but Tokyo Drift, died during the filming of Furious 7. The circumstances of his death (a car accident, the details of which are heartbreaking and awful) cast a shadow over the movie. Furious 7 was completed thanks to CGI, existing footage, and the help of Walker’s brothers, who served as stand-ins for the actor. The result is an installment in a franchise that has never been remotely concerned with reality now blurring the line between fact and fiction so heavily as to almost destroy the fourth wall. The loss of Walker is palpable on all of the actors’ faces, and the last 20 minutes of the film are essentially an homage to him. From a narrative perspective, it makes little sense, but the tribute does not feel out of place.

That is the problem with the Furious series. I very much want to write it off as blindingly stupid, but every now and then it will do something delightful or brilliant or downright heartwarming. Take its treatment of women – a universally problematic issue for the entire genre, the films aren’t entirely terrible with their portrayal of female characters.

In one scene, a female lead who has lost her memory and was believed dead (which isn’t how amnesia works, or how death certificates work, or how plot structure works, but whatever), returns and encounters her former lover. He never makes a single overture or move to the woman he adores – he’s well aware that to her, he’s a veritable stranger. He does look at her longingly, but stops when she tells him to.

Later, when her memory returns, she asks him why he didn’t tell her about their relationship (which was far more intimate than the audience is led to believe).

“Because you can’t tell someone they love you,” he says.

Here, in the midst of a positively moronic action movie is one of the most nuanced and beautiful examples of understanding consent I’ve seen in pop culture. But while the series avoids the usual tropes of threatening women with sexual violence, it still manages to reduce some powerful female characters to merely being tools of reproduction or emotional weak spots for male protagonists. It seems absurd to be disappointed in a franchise that is essentially a really long Hot Wheels commercial for not consistently writing awesome parts for women, but it’s hard not to hold Furious to a different standard. The main cast is more diverse than other mainstream action films – characters code-switch between English and Portuguese and Spanish; they have ties to Brazil and Cuba and the DR. They are connected to the world around them, and haven’t been scrubbed of cultural identity for the comfort of white audiences (one scene features The Rock leading a group of tween girls in the haka before their little league soccer game. The representation isn’t clear or perfect – dance is Maori, and someone describes The Rock as “Samoan Thor” – but it is still miles ahead of most other films of the genre.)

I am touched and impressed, and then everyone starts jumping out of cars and catching one another mid-air and I feel my brain cells atrophying.

In short, nothing about these movies is simple. And after watching all eight of them (I’ve said the phrase “Tokyo Drift” more times than anyone who was actually involved in the making of the film, so I’ve decided this counts as seeing it), I assure you they are paradoxically more complex and far more stupid than you could ever imagine. In the end, I am left not knowing what to do.

These movies are absolutely asinine. I can’t stop talking about them. Please help.