Moving On.

We’ve moved. After 7 years in the townhome we rented – longer than I’ve lived anywhere in my entire, Rand and I moved into our first house. It wasn’t far – just across town, but I was surprised by how hard it was, especially for two people who were constantly moving from one city to the next. I realized that it wasn’t the neighborhood I was having trouble saying goodbye to, but that chapter of my life. I took down a photo of someone I’m no longer friends with, and realized I will never put it – or any photo of her – back up on my walls.

People and cities change and there’s only so much time you can spend grieving what’s gone.

“This town got away from me,” a friend told us, just before he left Seattle for New York. His apartment in Brooklyn is barely more expensive than the one he had here, but it’s substantially bigger.

My cousin, who is moving to Queens next month, tells me how New York isn’t unreasonable anymore when compared with Seattle. I realize that I can try to hold on to this town, but not to the people in it. I watch tented cities build up on the side of the freeway, and feel a mix of immeasurable guilt and gratitude at being a homeowner. I ask Rand if we can afford our new place.

“I’m doing my best,” he tells me.

Every time something breaks, or needs replacing, or a support beam turns out to be just a collection of rats standing one on top of the other, I feel my chest tighten. And then I feel guilty for feeling guilty.

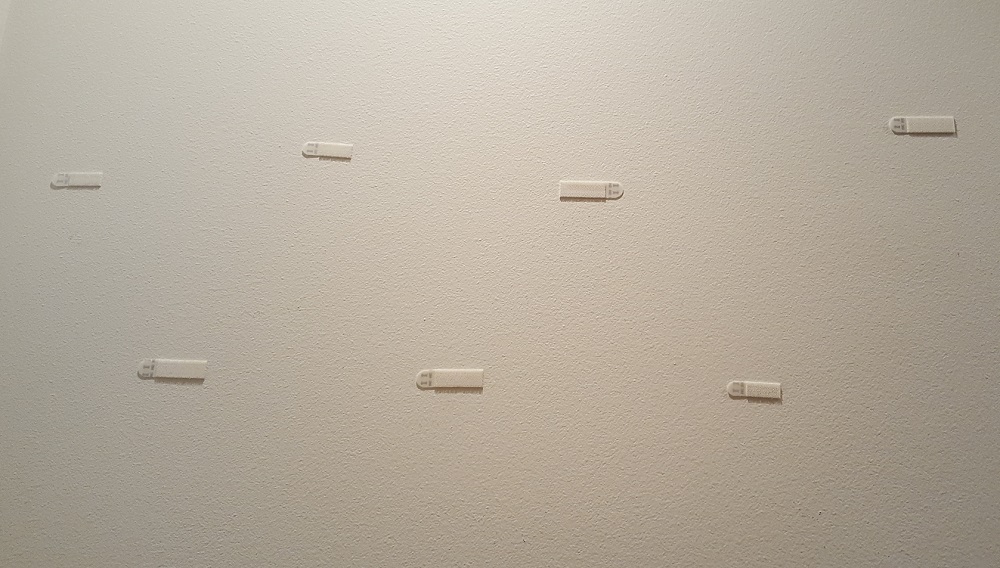

When I think about returning home from a trip, I still think about the old place where we once lived. Like so many things that we’ve long outgrown, I forget the bad. I don’t remember how impractical and small it was – I simply miss it. I miss our winding stairwell, and the photos that lined it. I miss our too-cramped living room. I miss the weird collection of paintings and souvenirs and tchotchkes that made it home.

I miss my dad.

I packed up photos of him, and thought about how this new home we’ve found was made possible in part by the inheritance he left us. I could once again see that line of demarcation between the past, when my father was alive, and the world we live in now, the one he’s not a part of. Our old home straddled that line. This new one doesn’t. It’s the last the gift he’ll ever give us.

For the first few months in our new place, I spent my days crying. Rand watched me, unsure of what to do or say, and also, I think, understandably hurt.

I bought you this house and all you do is cry in it.

He never said that. Rand would never say anything like that. But I thought it for him.

The people you think will always be there for you – the ones who you assume are a fixture in your life, will suddenly, through choice or circumstance, be gone. The adage isn’t a lie – you really can’t go home again, because either it’s changed or you have. I pack up photos of babies that are no longer babies, of couples newly divorced, of people now gone.

I walk around the house that my dad and my husband and in some small part I helped build. We had a small window in which we could buy – a small window of time when all the pieces fell into place. Two book deals. A stock sale. An inheritance. I think of every sacrifice my husband and father ever made for me and how some people work just as hard – or harder – and it’s not enough. I know I don’t deserve this house. I know I don’t deserve a lot of things that I’ve been graced with.

You put your life in a box, and if you’re lucky, you have a nice, warm place to unpack it. In the end, the one thing that makes you truly feel at home is the one thing that’s never left you.

And you just have to hope that will always be true.

We are exceedingly fortunate that we were able to buy a home. 144 people died in homelessness in King County last year. This article outlines some resources if you see someone without shelter who looks like they might be in danger.