The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico

I broke my long-held rule about not taking photos of artwork while at The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. I don’t know if my views on the matter have changed or not. Perhaps they’ve shifted only slightly. I still get angry at people using flashes to light up ancient works, I still want to scream at the woman I saw at the Louvre pressing her cell phone against a canvas, I get annoyed when I’m are trying to appreciate the stillness of a painting to a soundtrack of endless clicks and beeps. But sometimes it’s okay, and there are no hard and fast rules for when I think that’s the case – like the oft-repeatedly refrain about pornography, I’ll know it when I see it.

For the record, non-flash photography is allowed in the O’Keeffe, but I waited until the galleries were empty to sneak a few sparse shots. Call me a hypocrite (I mean, I’ll punch you in the throat if you do, but go for it). My rules are malleable and my mind sometimes changes. Besides, photography was a recurring theme in the artist’s life. Her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, was a photographer and art dealer, as were many of her friends, including Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter. I have trouble imagining her yelling at me, but I’ve heard that her personality was abrasive, so it’s tough to say.

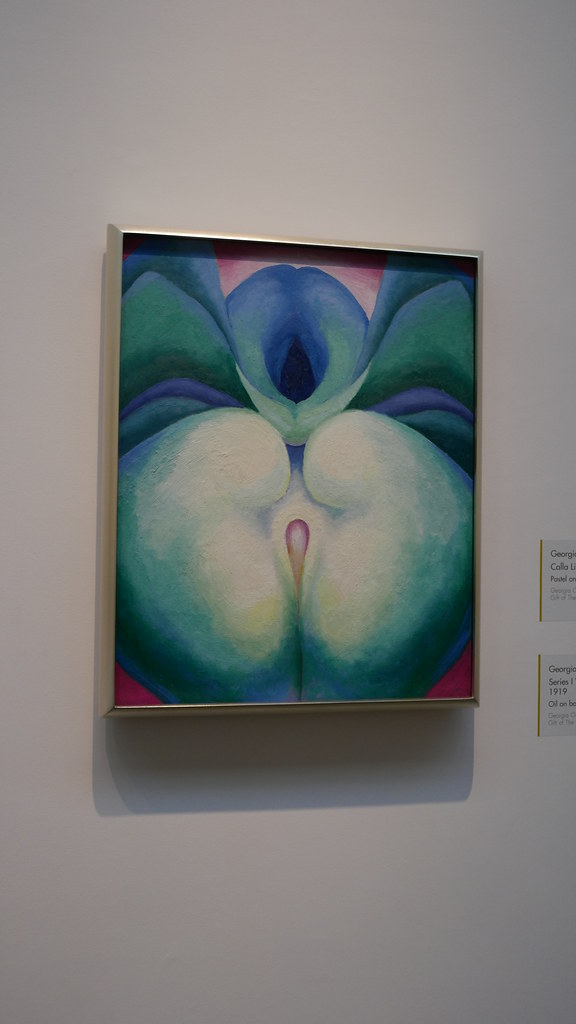

I remember when O’Keeffe died, or at least I think I do. I was five, and I marveled at her longevity – she lived to the ripe old age of 98. Her gigantic flowers meant that she was one of the first artists I could identify, and I felt a point of pride in the fact that she was a girl, like me, when so many of the masters were men (I was too young to understand the importance of representation, of seeing someone like yourself in a field where you didn’t think there was space for you). I didn’t know of all the scholars who felt that her creations hearkened to the vulva. In my younger years, I couldn’t see it. Now I laugh at what true innocence is.

I mean, come ON. This is an anatomical diagram.

O’Keeffe adamantly denied that her work intentionally referenced the female anatomy, and I wonder if she genuinely believed that or if she was just messing with everyone. Maybe it was subconscious on her part. Maybe it was a fantastic gag she was playing. “What? No. Heavens, no, those aren’t labia. What the hell is wrong with you?”

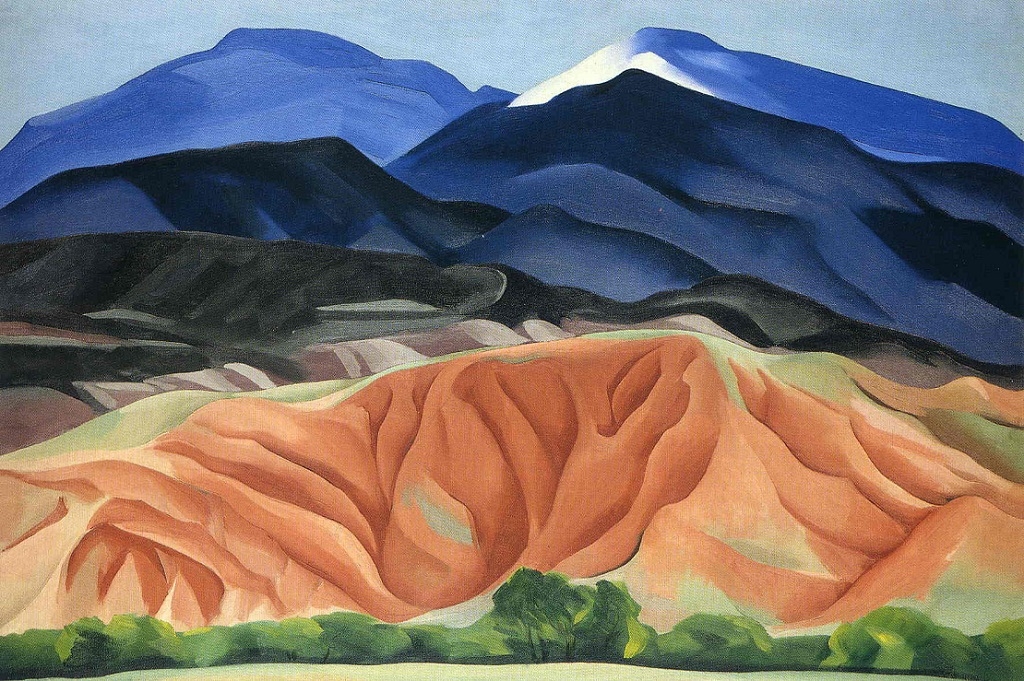

Her work extended far beyond her well-known blossoms. She is often regarded as the Mother of American Modernism (a title which I find rather amusing; O’Keeffe had no children, so American Modernism is an only child). She drew landscapes and cities, animal skulls and abstract forms.

This was from her “Pelvis Series” BUT NONE OF THIS IS ABOUT VAGINAS.

She lived in New Mexico for decades, and being there for the first time, I felt like I was seeing her paintings in context – the blue skies and the dusty hills. The entire state looks like an O’Keeffe painting. Or perhaps vice versa. I can’t really say.

One of her favorite subjects was Cerro Pedernal – a narrow mesa visible from her home at Ghost Ranch. You can see it in three of the paintings below:

She once said of it, “It’s my private mountain. It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.”

I find this mind-bogglingly arrogant quote to be endlessly charming. Upon O’Keeffe’s death, her ashes were scattered across the top of Pedernal. Perhaps the mountain never belonged to her, but she most certainly belongs to it.

I usually find museums dedicated to one artist to be a little stifling. But O’Keeffe was as dynamic as she was prolific. Her works are both immediately recognizable and yet dramatically different from one another. In nearly every one, I could see the influence of Santa Fe creeping in. Later, I watched the sun set, and it was like looking at a painting.