Slip Sliding Away

By the time we land in Seattle, I am tired of people asking about the contents of the plastic toolbox. Both Rand and I have carried it from my father’s tiny Bavarian village to Munich to Amsterdam and now home, each of us now acutely aware of how ill-suited a container it is for transportation. The handle is uncomfortable, and you have to dedicate an entire arm to its heft. It is meant to sit on a shelf, as it did in my father’s home, and not to be carried halfway across the world, while fending off questions from mostly well-intentioned travelers and flight crew.

“Oooh, is that a pet carrier?”

“What’s in the box?”

“You got your husband to carry your cosmetic case?”

Most of the time I just smile (even through the misogynistic interrogatives), or let Rand answer. I am exhausted from jet lag, from having finally seen my father’s grave three months after he died, because his funeral was the week of Christmas and I couldn’t make it out. From having walked around his workshop, a place I rarely ventured into when he was alive because it was his space and I didn’t want to annoy him, and now that he is gone his absence hangs in the air. The silence of the house without him in it is deafening. I spend every day of our trip anxiously awaiting seeing his grave, worried that the entire weight of his death will hit me when I finally see it. But instead of catharsis I’m left with a strange denouement, like when a sneeze almost comes to fruition and doesn’t, and you rub your nose, knowing the feeling will now take longer to dissipate. There is no release valve for my emotions. They don’t boil over, like I want them to – they simply stay at a low simmer, so that when someone snarkily asks me if I’d gone fishing, I’ve worn through my facade of cheerfulness.

“My father died. These are his photos.”

I don’t know how my reply will make the asker of this question feel. I am uncharacteristically unconcerned. I’m having trouble focusing on anything besides what I can remember about my father, and the remnants of his past that are tucked into a plastic box that everyone keeps asking me about.

At home, I open it up and smell the stale, musty scent of old photos. I breathe it in hoping I’ll somehow absorb something – my father’s memories, or some part of him that was stored in there like a horcrux. But I inhale nothing besides a dry and woodsy scent that I am convinced is what the 70s smelled like.

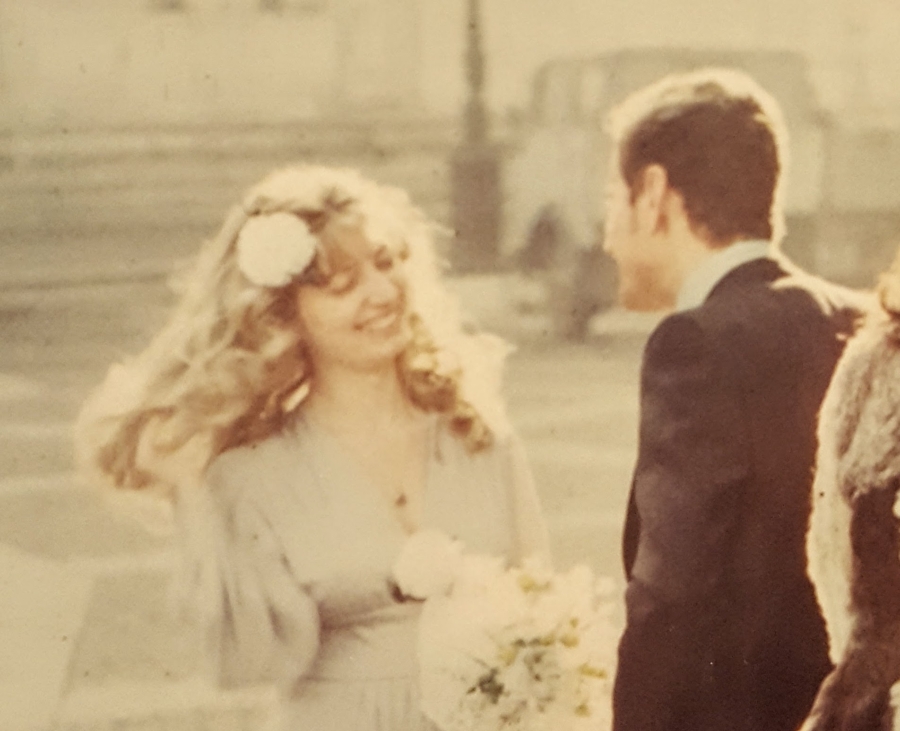

There are lots of slides. Tiny plastic transparencies that would be impossible to make out were it not for the slide viewer that my mother gave me a few months back, in a surprisingly prescient move. They are all meticulously organized, my father’s handwriting denoting location and date. “March 1977, Edward is 6 Months.” “Rome, Summer, 1978.” I put the slides in, and the viewer illuminates and magnifies the images. My family’s past lights up on a tiny screen in my hands.

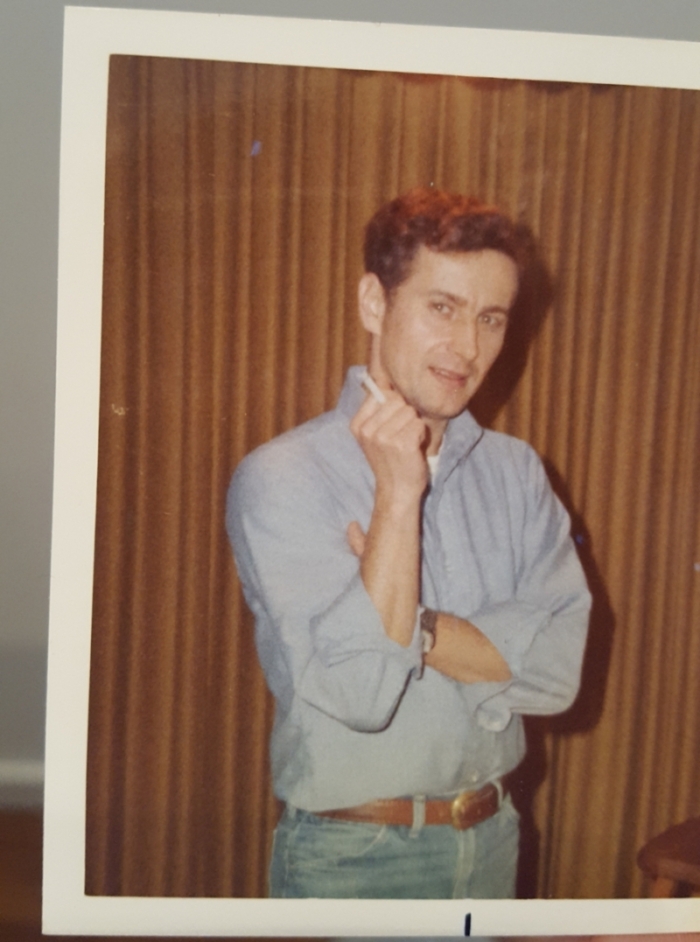

There are a few loose photos of my dad, but not many. Just enough to remind me of this seemingly impossible truth: once upon a time, my father was young and handsome and very much alive.

But more often than not, he is the photographer, and not the subject. And I try to discern all I can from that. Even if there aren’t enough tea leaves left to read.

I look at how he saw my mother.

My dad, when I knew him, always seemed annoyed by my mother’s antics. But the photos here suggest that there was a time when he didn’t mind so much. That perhaps for a little while, he understood her. Or at least he tried to.

I follow my brother from newborn to toddler, every moment of his life painstakingly documented until sometime after he was three, when my mother left my father for America.

The photos become more scarce as the years go by, and by the time I am born, my father does not have originals or negatives or meticulously organized slides. He has only the photos my mother sends to him, a disjointed hodgepodge of images of us, now in America. They are no longer linear. Time jumps around as I rifle through pictures that are in no discernible order. I am a newborn. I am five, riding my pink Huffy with its white training wheels. I am a year old and eating bread like it’s my job.

File this under: things that are in no way surprising at all.

My parents never lived together in my lifetime, at least, not that I can remember. They were always on separate continents, and when they divorced (sometime before I turned four), I remember processing the news with little discernible emotion. I’d never known them together, so their official split carried little weight. But flipping through slide after slide of the life they had together, I realize that my parents may have, for a brief glimmer of time, loved one another.

And this breaks my heart in way I hadn’t anticipated.

I ask my husband if it’s okay, and don’t elaborate. Even I am unclear what I’m referring to – I just want reassurance, which he is quick to offer. Everything is fine. My father was sick. He lived a relatively long time, all things considered. And yes, it was a good idea that he and my mother divorced.

“Your parents are the two most incompatible people who ever lived,” Rand says. “Honestly, it’s a miracle you even exist.”

He is loading the dishwasher, and pauses to look at me. “But I’m glad you do.”

With my brother, circa 1983. I am the one dressed like a rodeo clown.

He reminds me that they did and do love me. I nod. I place the slides – evidence that my parents were once married and maybe even a little happy – back into the box. They are part of an equation that yielded an improbable result.

My mother + my father = me.

And I remind myself that now that he’s gone, this doesn’t change.