The Decline of the Khmer Rouge, and Its Legacy

It’s funny (well, not funny, but you know – interesting) that even as I’m researching this stuff, I have trouble imagining how it happened. I saw first hand the aftermath of it, but some part of me still can’t wrap my head around it.

I guess I would just like to think that we live in a world where international organizations step in BEFORE genocide happens, but history has shown time and again that we don’t. A lot of the time, we just sit back and watch. When we do intervene, it’s usually for the wrong reasons. And sometimes our attempts just fail.

Still, it’s hard to look at the Khmer Rouge regime and not wonder: what the fuck were the rest of us doing? And … shit. I’ll get to it. But mostly, we first did a lot of nothing. Later, we’d help them out. Yeah. I know. I KNOW. It’s totally fucked up. Anyway, on to the decline of the Khmer Rouge. All the caveats I mentioned in earlier posts still stand. I’m an American. I’m not a historian. I tend to editorialize.

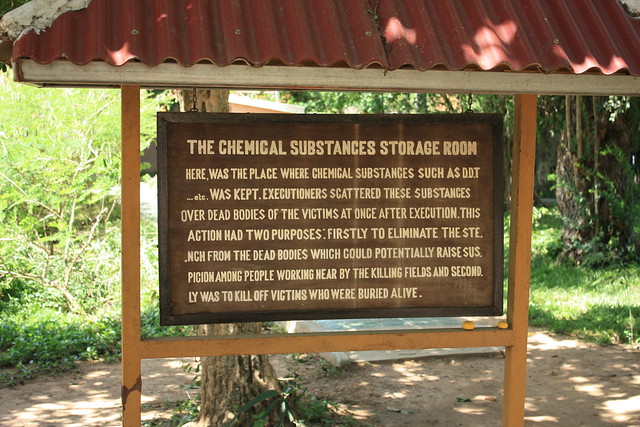

Sign at Choeung Ek Genocidal Center.

By the second half of the 1970s, the Khmer Rouge had all of the Cambodia people in a vice. People would be dragged off to Tuol Sleng Prison in Phnom Penh, where they were interrogated and tortured, then sent to the Killing Fields, where they were murdered in all kinds of horrific and creative ways (the Khmer Rouge didn’t like to waste bullets on executions), and dumped into mass graves.

The Khmer Rouge was a paranoid organization. They purged their ranks regularly, killing people who served the party dutifully for years. Soon, they began looking towards Vietnam, their former ally, with suspicion and hostility. I’ve tried to figure out precisely why this happened – they were, after all, in ideological agreement, right? As best as I can conclude, the higher ranks of the Khmer Rouge resented that they had needed Vietnam’s help to establish a Communist Party years prior (indeed, many of the KR troops had been trained by Vietnam). Their hostility towards Vietnam was almost a way of asserting their independence. A wide-scale proclamation of: “Look, I don’t fucking need you anymore.”

The tensions were exacerbated by the fact that Cambodia was receiving aid from China, and Vietnam was receiving aid from the USSR (the two leading Communist superpowers that were competing for dominance on the world stage). “Cambodia and Vietnam were now the pawns of a Chinese-Soviet rivalry, not unlike when the U.S. and U.S.S.R. took advantage of the regional instability of the Vietnam War to further their own Cold War interests.”

There was more: the Khmer Rouge wanted to expand their empire – they wanted to take over parts of Thailand and Vietnam, and often sent troops into border villages, massacring thousands of unarmed people, including children.

By the end of 1977, there was an all-out conflict between the two countries. Tens of thousands of people died. Vietnam had begun a preemptive attack on the country – they moved over the border and into several villages, but they soon retreated.

The Khmer Rouge saw this as a victory – it wasn’t. The Vietnamese were simply playing the long game. They’d captured numerous Khmer Rouge defectors who had fled to the villages, fearing a purge. Through them, the Vietnamese could take a deeper look at the flaws of the KR government. They could also groom these officers to be leaders in a new, Vietnamese-backed Cambodian government (and soon, they would do exactly that).

On Christmas Day, 1978, Vietnamese troops once again descended on Cambodia. In two weeks, they would successfully take the capitol. The Khmer Rouge leaders – including Pol Pot – fled (many of them would die decades later, as old, fat men, having lived long, comfortable lives. If that sounds sickening, it’s because it is: very few were held accountable for their crimes).

Vietnam would install a new government – the People’s Republic of Kampuchea. Some of the former Khmer Rouge defectors (the ones they had captured from the villages and groomed the year before) were installed as leaders.

Now – here’s where things get sort of confusing and messed up (what’s that? You don’t understand how things could get even more fucked up than the systematic killing of millions? Just wait). On the international stage, most countries didn’t identify the Khmer Rouge as being Communist. I know that’s ridiculous – clearly they were (or they were trying to be, anyway. Ideologically, I don’t really know what the hell they were). They were receiving aid from China, and all the Year Zero bullshit was in hopes of creating a Maoist/Stalinist utopia (which is an oxymoron if I’ve ever heard one, but again – I’m editorializing because I’ve been writing about this for days, and I’m now officially fucking pissed. Sorry.) But – I think I read this correctly – Pol Pot only claimed that the country was Communist once in a public address. The rest of the world, I think, regarded the KR as Communism-lite.

But now Vietnam – Communist Vietnam – had invaded the country and installed a new government. To the international community, it looked like the Khmer Rouge had been wronged. They continued to recognize the KR as the only real government of Cambodia (I shit you not) – a claim that was legitimized by an alliance with the still-in-exile Prince (remember him? He was the one who didn’t want to sour relations with Vietnam in the first place, which led to the coup, which in turn led to the rise of the Khmer Rouge).

The KR even had a UN seat and received international financial aid.

The U.S. was instrumental in making all of this happen (China helped, too). We were motivated by two reasons:

- We didn’t want to support our former foe, Vietnam.

- We finally had some good relationships with countries in this part of the world – namely China, who was supporting the KR. So we weren’t going to start screwing that up. Besides, our intervention in Vietnam had made us more than a little skittish.

Other first world countries recognized the Khmer Rouge as the true government of Cambodia. Among them: Australia, the U.K., Germany, and France.

This went on for years. The U.S. literally sent millions of dollars in aid to the Khmer Rouge while at the same time putting an embargo against the new Cambodian government. The KR was able to rebuild its forces, while U.S. media outlets downplayed the atrocities that had occurred. (If you want to read more about this, check out this article from the now-defunct Covert Action Quarterly, from 1997. I initially thought that it was some sort of conspiracy rag, but after a bit of research, it seems pretty legit).

In the early 80s, the KR even went so far as to denounce Communism, and began spouting rhetoric against the new Vietnamese-backed government. (Just a few years before, they’d murdered anyone who they believed had any ties to the U.S. or the west.) Around this time, Vietnam pulled out of Cambodia.

The forces of the Khmer Rouge (still supported by the U.S.) continued to fight against the new Cambodian government. In the early 90s, the UN attempted to establish peace agreements between all the Cambodian parties, but the KR refused to agree to them (demilitarization was part of the agreement).

It wasn’t until Cambodian refugees began settling in America that word began to spread about what happened. In 1994 the U.S., under Clinton, would finally change its policy towards Cambodia. The Cambodian Genocide Justice Act was passed, providing funding into researching the crimes of the Khmer Rouge and bringing perpetrators to justice, and aid was restored to the struggling country. In that same year, the Cambodian Government outlawed the Khmer Rouge.

The Buddhist stupa at Choeung Ek, where the bodies of nearly 9,000 people – all victims of the Khmer Rouge – were discovered.

By then, the party had mostly splintered apart. Many of its leaders had fled, and very few were apprehended. Pol Pot himself died under house arrest a few years later (as I noted, he was old and fat and happy. One can only hope there is a hell.)

So what of Cambodia today?

The UN had helped to facilitate elections in the country beginning in the early 90s, and the country’s national assembly voted to restore the monarchy. Prince Norodom returned to the throne, but would abdicate a few years later (he would die in 2012), and his son would become king.

The King is the head of state, but it’s kind of titular, like in the United Kingdom. There are two houses that make up the Cambodia Parliament. The lower house consists of the National Assembly, which appoints a Prime Minister as head of the government (it sounds a little like the way that British Parliament works). The upper house is the Senate.

The current Prime Minister is Hun Sen. He has held office since 1985, and was one of the Khmer Rouge defectors who was trained and installed by the Vietnamese government.

The Khmer Rouge is gone, but the scars they left on the country remain. An entire generation of professionals and artists was essentially wiped out. There are few old people in Cambodia – only 3.6% of the population is over the age of 65 (by contrast, 12.6% of the U.S. population is over the age of 65). The country is incredibly young – the mean age in Cambodia is just under 22 years old, about 15 years younger than the median age in the United States. If you see anyone over the age of 50, you know: they’ve seen some serious shit.

To this day, there remains a lot of governmental corruption. Sex trafficking is rampant, and many media outlets face restrictions and censorship. Poverty remains a huge problem – most Cambodians live on less than $2 a day.

It is a profoundly haunting and heartbreaking place.

And yet, miraculously, in spite of all of that, I can’t wait to go back.

Leave a Comment