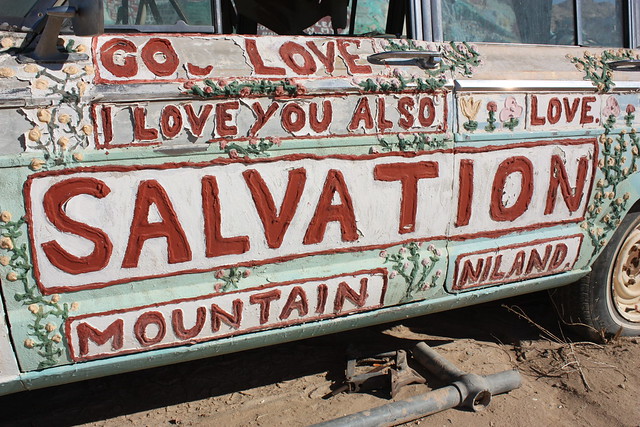

Salvation Mountain, Niland, California

Salvation Mountain, California.

Unless we’re talking about poltergeists or the healing power of cupcakes, I could not be described as a believer. I can’t even claim that I’m spiritual and not religious, because I’m not even that. The only thing that comes close in my life is my tendency to say “HOLY CATS” when I’m shocked about something, which brings to mind a rather delightful image of a higher power of the feline persuasion.

Even though I grew up Catholic, whenever we visit a temple or a church or some place of worship, I feel like a stranger looking in. Some things are familiar to me, and I can still recite the rosary (albeit only in Italian, and with a few mistakes).

But that’s it, really.

That’s not to say I don’t believe in anything. I do. I believe in lots of stuff.

I believe in dessert after any given meal, and occasionally before.

I believe that people should be able to marry whoever they want. If there is a higher power, I suspect it probably doesn’t give two shits about that.

I believe in over-tipping people who work in the restaurant industry. Or anyone, really.

Mostly, I just believe that we should all be excellent to each other.

So it seems that all the religion I need comes from Bill and Ted. (Party on, dudes.)

But I understand that might not be enough for other people. So if someone wanted to, say, to build a massive monument to remind us that god wants us to all love one another, I can totally get behind that. Because I feel like that’s just another way of saying “Be excellent to each other.”

That’s what Salvation Mountain is.

It feels like it sits at the edge of civilization. Nearby is a cluster of encampments called “Slab City.” It’s one of the few decommissioned and uncontrolled stretches of land in the U.S. There are no amenities: no running water or electricity, no sewers or toilets, no trash services.

Slab City.

Truthfully, it would all feel a little bit Mad Max-ish were it not for the cheerful structure (because really, it’s more that than it is a mountain) that sits on the nearby hillside.

We drove past the encampment, on a long stretch of cracked highway. A warm wind occasionally rolled through, but other than that, it was still and quiet. Everything around us – the hills, the roads, the endless fields of dust – seemed to be the exact same dull color, as though someone had put a sepia filter on this corner of the world.

Everything except for the mountain, of course.

It shot out of the ground like a technicolor confection, a melted pack of crayons on a brown-paper bag.

The mountain was started by Leonard Knight in the mid-1980s. Knight was a devoutly religious man, and his beliefs were simple: “accept Jesus into your heart, repent your sins, and be saved.” He spoke to numerous church leaders, all of whom resisted Knight’s doctrine, explaining that it wasn’t that simple. He argued that it was, and searched for a way to share his belief with the masses.

His original endeavor was an ill-fated hot-air balloon that never came to pass. The balloon kept ripping every time Knight tried to launch it. Disheartened, he decided to leave the area of Southern California in which he now found himself. He took a half bag of cement and a few cans and decided to created a small monument before departing.

Time passed, and slowly, the monument grew. Knight added more cement, sand, and paint, until the mountain reached a towering height of 50 feet. And then, one day, four years later, it collapsed in a heap of rubble.

Undeterred, Knight started again, this time determined to make his mountain more structurally sound. He used less sand and more cement. He incorporated straw and adobe and clay. And he used a whole lotta paint. An estimated 100,000 gallons or more.

The structure met resistance from county supervisors. The mountain was built on government land, and there were concerns that the paint might be toxic. The plan was to haul the entire thing to a nearby dump. Local residents stepped in to stop the destruction of Knight’s monument; new environmental tests proved that the mountain wasn’t toxic, and the site was eventually declared a site worthy of preservation and protection by the Folk Art Society of America.

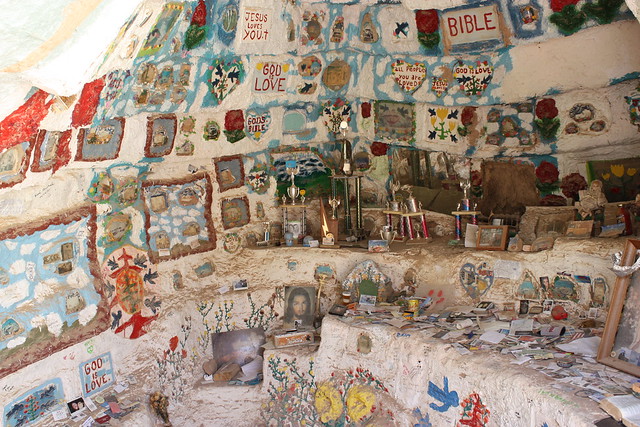

Leonard Knight kept adding to his monument for many years, leading to the sort of patchwork aesthetic it now has. It reminded me of a quilt that was at my grandmother’s house when I was a kid, that now lays over the back of my chair in my living room. A sun-bleached-but-still-vivid mix of texture and color.

The message, now, as always, is simple. It’s about love.

Even though I’m not religious, I can get behind that.

I think we all could.

There is a small sign at the entrance to the mountain that reads “Stay on the yellow brick road.” And so we followed the golden swath of paint as it wound its way up the mountain.

This hurts my heart a little bit.

There is no railing, and there are places where you could easily slide off if you are not careful. But if you step lightly and mindfully (with a tight grip on any squirmy wee ones in your company), you can make it up to the top and enjoy a view that stretches out past Slab City to the dusty horizon.

There is more to see than just the mountain itself. Knight began creating more structures alongside it (the “museum” and the “hogan”) – which tell a bit about the history of how the Salvation Mountain came to be.

Out in front there are a few old vehicles, similarly covered in bible verses.

–

Salvation Mountain is still a work in progress. There are groups of volunteers who continue to add to the mountain in same way that Knight did.

When we visited last month, we were told that Knight was convalescing at a care center nearby, and that every now and then, someone drove him out to visit his creation. It’s taken me a while to get around to writing this post, but my timing feels auspicious – I just learned that Knight passed away yesterday.

But his mountain remains a bright spot in the landscape, as does his message. And while it isn’t exactly my doctrine, it’s one that I can get behind.

Leave a Comment