The Magic Gardens, Philadelphia

–

The thing that I love about humanity, besides Thai food and the tendency to dress our young up as animals, is our commitment to the arts. That as a species, as soon as our basic needs are met (and even if they aren’t) we all hellbent on writing and composing and painting and sculpting and carving and decoupaging and etching and crocheting and just making things.

We are the species responsible for the Bedazzler and the Eiffel Tower, which is just kind of wonderful to think about.

The desire to create has probably been going on since the beginning of time. I like to think that before the advent of language, some prehistoric couple was having a huge fight because one of them spent too much time on cave paintings and not enough time having meaningful discussions grunts about their future together.

I find this idea comforting. The media may change, but we always have and always will make art. Some of it will be great, and some of it will be terrible, and no one will be able to definitively say which is which.

Except for the work of Bob Ross, because I’m sure we can all agree that he was a genius. (Wherever you are now, Bob, I hope you’re surrounded by a forest of happy little trees.)

While I was in Philadelphia, numerous folks told me to check out the Magic Gardens. Just watching people struggle to explain what the gardens were was a delight in and of itself.

“It’s a bunch of mosaics, but they’re really textural …”

“He began tiling his house, and it just sort of spread.”

“He just took a bunch of stuff and … and … Ugh. Just go see them.”

So I did. And, man, are they hard to describe. The best I can do is this: they are a testament to mankind’s commitment to create.

–

With whatever you can find.

–

Even if not everyone likes it.

–

Even if the result is a little unorthodox. And pointy at parts.

–

If you are walking down South Street it is virtually impossible to miss the gardens. They cover almost half a city block, and twinkle in the daylight (courtesy of several thousand embedded shards of mirror.)

–

–

–

They are the work of artist Isaiah Zagar. Zagar and his wife moved to Philly (his birthplace) in the 1960s, after spending several years in Peru with the Peace Corps. Upon returning to the U.S., they took up residence in Philly’s South Street neighborhood, which was undergoing an exodus. People were moving out of the area, and buildings were being abandoned and falling into disrepair.

–

He began covering the walls and ceilings of his home in mosaic tiles, and got permission to continue his work onto an adjacent lot (which he did not own).

An interior wall at the Magic Gardens.

–

What was once Isaiah Zagar’s garage.

–

–

By 2002, the neighborhood had changed drastically, and property values were rising. The owner of the lot decided to sell, and Zagar’s creation was at risk of being destroyed by developers.

–

–

–

–

Fortunately, the people of Philadelphia realized how important Zagar’s opus was to their city, and quickly intervened. A non-profit organization was established – Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens – with the mission of preserving and promoting Zagar’s work. In addition to the gardens, he’s covered more than 200 walls in Philadelphia with his mosaics.

One of Zagar’s mosaics on South Street.

–

A decorated facade.

–

The aesthetic of his work is unique. It’s South American folk art meets Antonio Gaudi – a mixture of smooth and rough, of jagged corners and rounded edges. The scene is occasionally chaotic and overwhelming but somehow, somehow, it still manages to feel harmonious and completely organic. More than once, I felt like I was wandering in the gut of some giant, other-worldly beast. It was like a crude version of Park Guell in Spain (and I mean that as a compliment).

–

I found myself captivated by the details. I love details. It’s actually a problem, because it means I often fail to see the big picture.

–

I needed to consciously remind myself to step back and look at an entire wall – to force myself to see all of the vignette, and not just be captivated with one tiny corner of it.

–

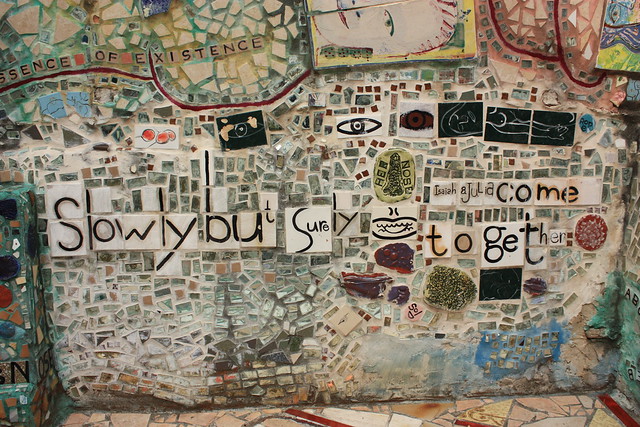

The gardens have a delightful mix of purpose: they are open to the public, and they belong to the city, yet they feel incredibly personal. The tiles tell portions of Zagar’s life story, and include names and sketches of people who are important to him. Much of it is autobiographical.

This wall was about his wife: “Slowly but surely Isaiah and Julia come together.”

–

This one, too.

–

Despite this, as a visitor you don’t feel excluded from his personal story. You feel drawn into it.

Sometimes literally.

–

I did.

–

Zagar is a recycler; many of his materials are found or foraged. Reduce his work to its bare components, and you have a pile of things that most people would overlook or throw away.

–

He creates from essentially nothing.

–

–

But can’t that be said of all art? It all starts out as just … stuff. Paint and canvas, ink and paper. But we’re compelled, as humans, to turn them into something. We create. It’s what we do.

–

And when we’re done? We find another wall, or another empty lot, or a scrap of paper, and we do it all again.

—————

Leave a Comment