What Happened When I Tried Talking to Twitter Abusers

Trigger warning: please note that this is a blog post about online abuse, and includes screen caps of tweets sent to me. Graphic threats and abusive, hateful language toward women appear therein.

A few weeks ago, I gave a keynote talk at World Domination Summit in Portland. The thesis: while we regard online misogyny and abuse of women as something wholly separate and different from its so-called “real-world” counterparts, these are all components of the same system. We dismiss sexual harassment that happens on the internet in the exact same way that we dismiss sexual harassment that happens face-to-face, even though these experiences are often just as bad – if not worse – for the victim, often due to the mechanics of the anonymity of the internet.

Women – both online and off – are told that we are overreacting, that we brought this abuse upon ourselves, that we can just leave the platform or get a new job, that the threats aren’t real, and a litany of other arguments meant to cause us to question our own realities and experiences. Teach a woman that she can’t trust herself and she becomes infinitely easier to abuse. Those of us who do speak up are labeled difficult, humorless, shrill, caustic; not only are women mistreated, but a system is in place to ensure that they can’t call out that abuse without doing more damage to themselves.

I can give talks to large crowds – I just spend way too much time preparing for them; this was no exception. For months leading up to the talk, I frantically worked on slides, I created and scrapped outline after outline, I poured through academic journals, and – most harrowing of all – I spent time talking to online abusers on Twitter.

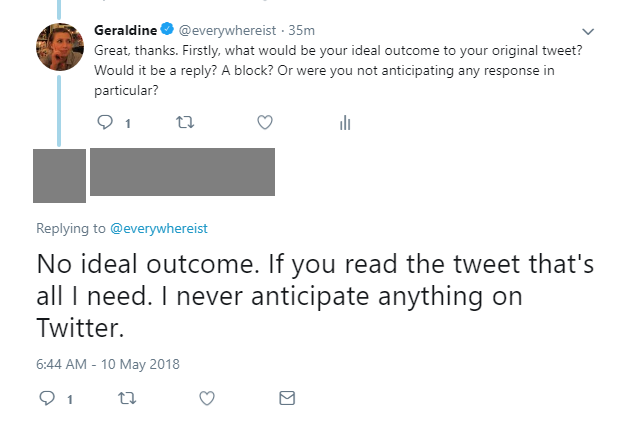

It was illuminating, though perhaps not for the reasons one would think. There was no common ground reached, no epiphanies that we were all just people with different views. Quite the opposite, really: I realized that these individuals did not and would not care about my feelings, no matter how long we talked.

As I told the audience of WDS, I do not recommend this exercise. “Don’t feed the trolls” is an oft-quoted refrain whenever online abuse comes up, but it is far too simple, and as the (anonymous) writer of this brilliant piece notes, it is hardly effective. We now are so disinclined to feed “trolls” (a term that I reject in this instance – these are abusers, pure and simple, not trolls) that we’ve created a strange system where we don’t even acknowledge the pain of their victims, or, if we are the victims, where we fail to acknowledge the pain that they have caused us. But the root of the argument holds true: online abusers feed off attention and the knowledge that they’ve caused their victims pain.

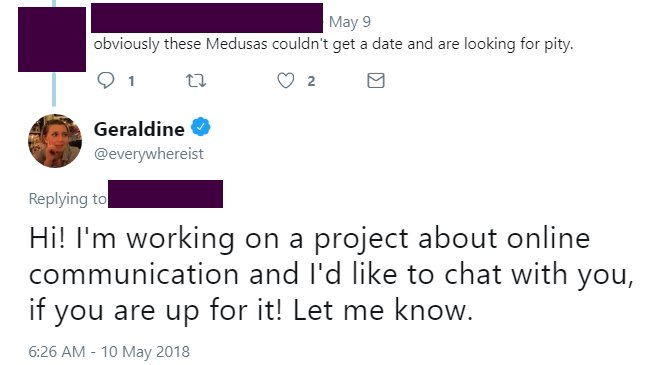

This individual noted that they had no ideal outcome in mind for their tweet – they just wanted to be sure I saw it.

One tactic I’ve often seen people take (which I’ve also tried) is to reason with online attackers, to make them acutely aware of the fact that there is a human at the other end of their attacks to whom they are causing pain. This rarely works because, as one study found, individuals who were more likely to engage in “trolling” behaviors were more likely to have psychopathic and sadistic traits. By telling them about the pain they were experiencing, their victims had given the trolls precisely what they wanted.

I realized I had to tread carefully – I needed to not get upset by their words (or if I did, not let it show), and not give them any kind of reaction they might find gratifying. Fighting back, making arguments, disagreeing – all of this would simply feed into their goals or incite their wrath. Instead I found myself almost numbly engaging them, in the way I do with volatile people I’ve encountered in real life. Anyone who argues that online abuse feels different than in-person abuse is kidding themselves.

The vast majority of my interactions were frustrating. Some didn’t reply at all, or disappeared instantly the moment I engaged them – blocking me, even though they were the ones who had attacked me initially.

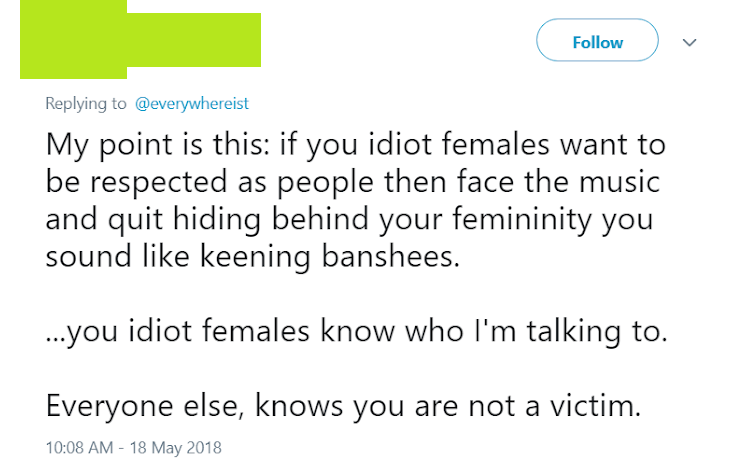

With others, it was like trying to converse with a piercing alarm. Once they realized a live human being had seen their initial tweet, they unleashed a torrent of insults, in a sort of frenzied, rapid-fire slew of hate and misogyny. This wasn’t about conversation. This wasn’t about intelligent debate. This wasn’t even really about me. This was about unleashing all of the hate they’d accrued for women over the years.

Like, what is this guy even talking about? WHO IS HE TALKING TO? Because I don’t think this had to do with me.

I also learned – rather quickly, though not quickly enough – to only engage people in my mentions. I had started trying to talk to people who were harassing my friends or prominent women, but soon found that my engagement galvanized their hate against their initial target. The safer option was to talk to my own abusers, ensuring that I would be the recipient of such a reaction. (I’m a white, able-bodied, cis-gendered woman. There’s a lot of privilege that comes with that.)

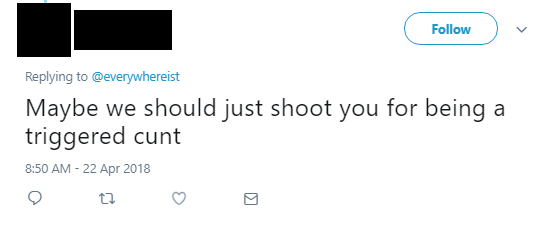

It should be noted that the people I chose to speak to were not the authors of the most vitriolic hate in my mentions. At the request of several people who care about my well-being, I didn’t speak to anyone who’d threatened anything too graphic or terrifying. For example, per Rand’s request, I didn’t talk to this guy:

I reported this to Twitter. They made him delete the tweet but his account is still active.

–

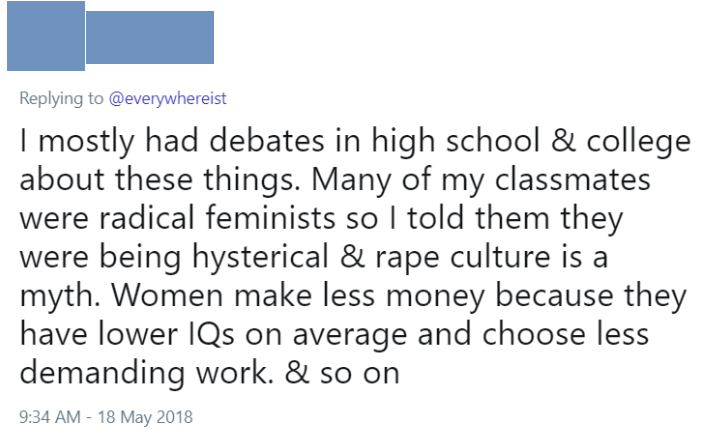

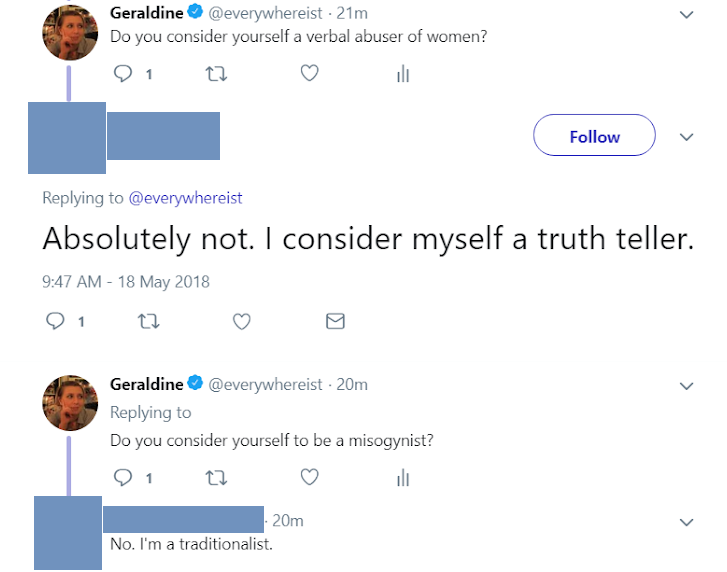

And after more than a dozen of these conversations, I found some commonalities with the individuals I spoke to.

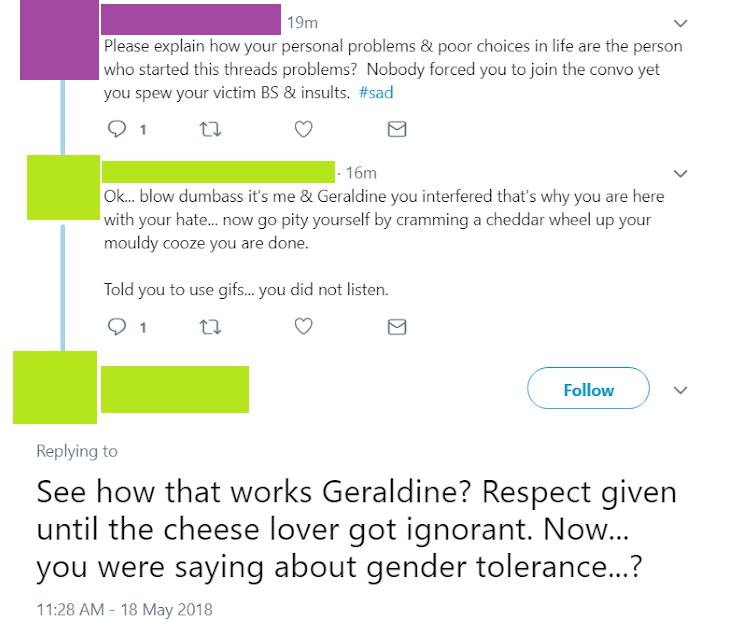

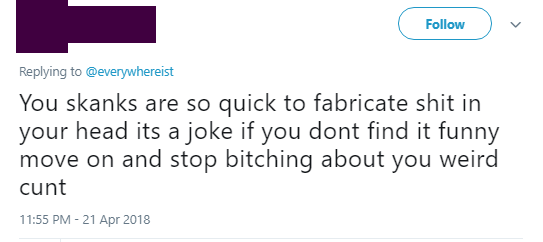

- None of these people considered themselves misogynists. I asked them directly, and the responses to this (and to whether or not they considered themselves to be abusers) was a resounding “no.” Many of them made arguments that they treated men and women equally (something that they repeated to me ad nauseum, along with, rather inexplicably, their military service, and the fact that they were fathers). One guy told me that he wasn’t a misogynist or an abuser of women, and literally three minutes later he tweeted this to a woman (in purple below) who called him out:

–

–

While this level of cognitive dissonance is jarring, it’s not that unusual when it comes to how people regard their own hateful beliefs. Think about many times someone has been caught on video verbally abusing a person of color, only to immediately release a statement saying, “I am not a racist.” Because the sort of self-scrutiny that allows a person to see their own capacity for hate usually also means they are working on that hate.

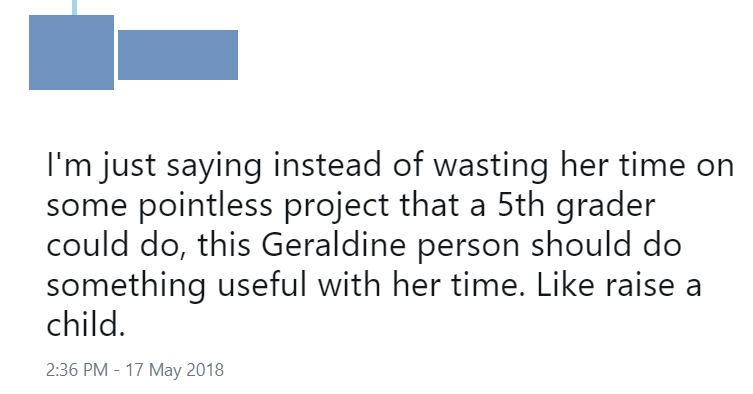

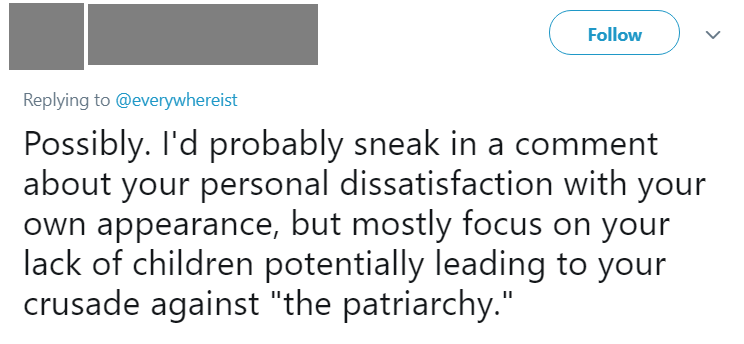

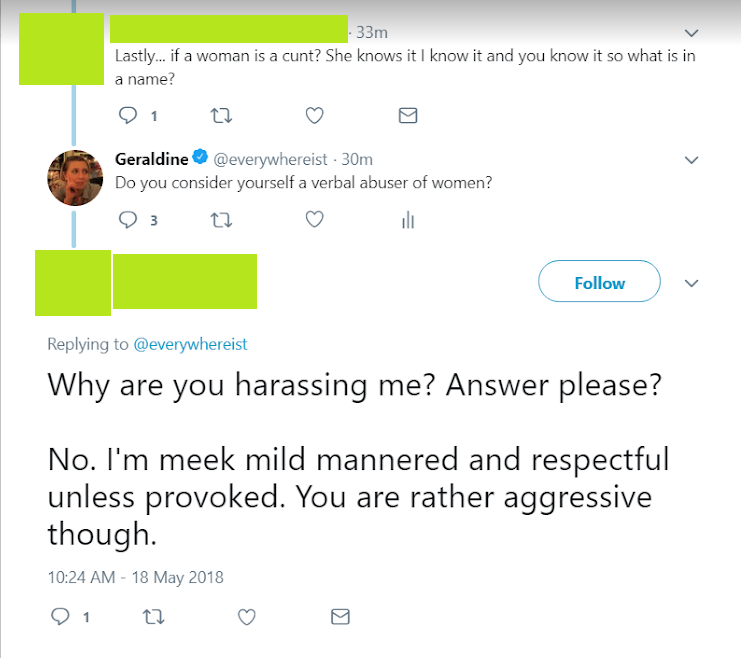

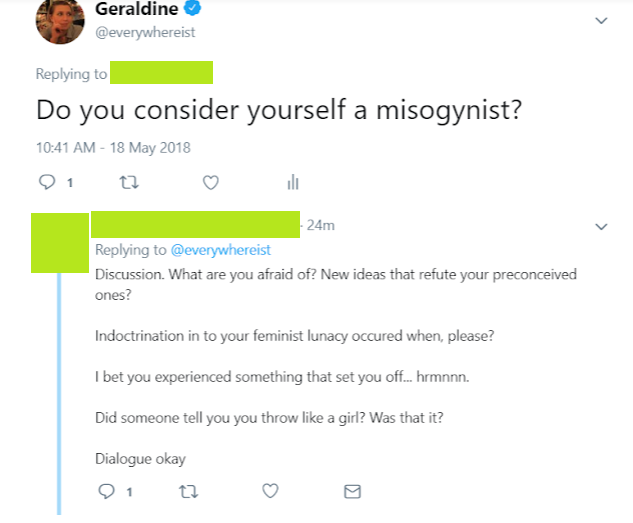

– - They later doubled-down on the sexist insults. When I asked them about their behavior, almost all of these individuals immediately got defensive, tried to obfuscate the issue, and when none of that worked, they doubled down on their attacks. And the way in which they did so revealed that their initial sexist or misogynist tweet to me was probably not a fluke. I was told that I’d turned to feminism because of some pitiful insult that I couldn’t handle (like someone had told me that I “threw like a girl” – thereby mitigating the scope of sexism that women deal with every day and framing feminism as something reactionary and vengeful), that I was profoundly unhappy with how I looked, that I was angry at men and if only I’d had a couple of children, all of that would change.

–

– And lest anyone forget, they are not misogynists:

And lest anyone forget, they are not misogynists: –

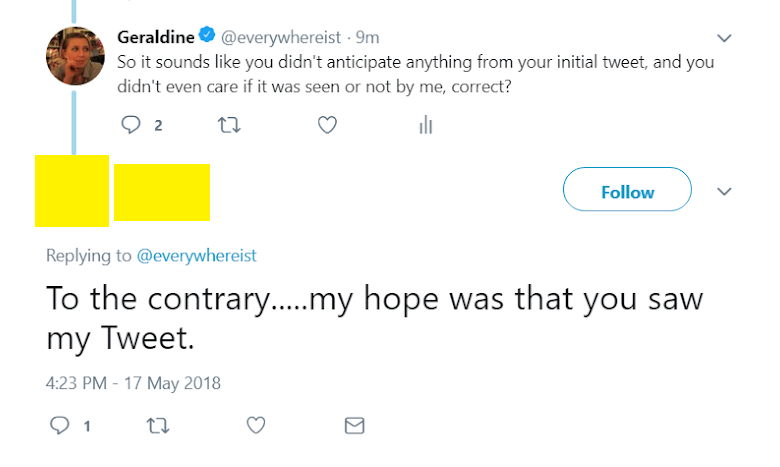

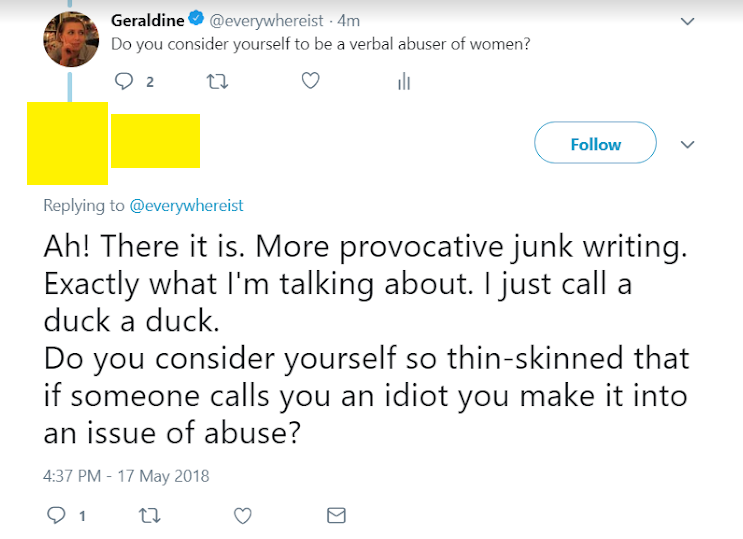

– - According to them, all of this was my fault. I was told repeatedly that my choice to be vocal on issues of politics and feminism opened me up to the bevy of insults that I’d received, and if I hadn’t chosen to talk about those issues, then this wouldn’t have happened. I’d expressed my views in a public forum, and now I couldn’t handle a little criticism that resulted from that.

This guy has called women the c-word and the b-word, sent a photo of a crack pipe to a black woman whose views he disagreed with, regularly threatens people on Twitter, and has since blocked me. But apparently he is not abusive and I am thin-skinned.

–

The thing is, as a writer, I can handle criticism. Most writers can, because (and many of us will tell you this) even the most scathing Kirkus review isn’t quite as awful as what goes on in our heads.

–

But this isn’t criticism:

Telling a woman that she’s ugly and repellent and that she holds her beliefs because she’s angry that she’s barren doesn’t actually indict or refute her arguments in any way. It doesn’t create a dialogue. It’s just designed to silence women they disagree with, and doing that doesn’t mean that they’ve won the debate or proved their point. That isn’t criticism or debate. It’s just abuse.

– - This wasn’t harassment; I’m just too sensitive. As I noted above, women who call out harassment are often told that their situation isn’t abusive or problematic – they’re just perceiving it the wrong way. It’s gaslighting at it’s finest, because it means that victims often don’t even realize that we’re victims – we’re just left feeling terrible, and wondering how or why we provoked the reaction that we did. Because women are so often blamed for their own harassment, and those that speak out against it are often vilified more than their harassers, most of this abuse goes unreported. What’s amazing is to be told that we’re fabricating sexism and abuse by people who, in that very same breath, abuse us.

–

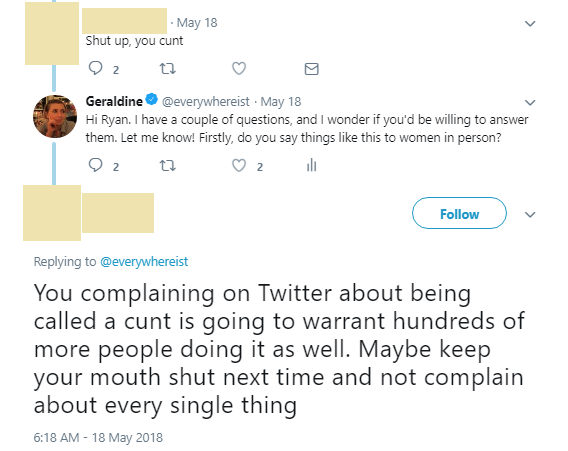

– - They accused me of harassing them. As I noted above, I didn’t fight back or disagree once the individuals agreed to talk to me. But when they strayed from the questions, or failed to answer them, I steered them back to my initial query, and I suspect that even that sort of minimal pushback was new to them (most abusers aren’t used to any sort of resistance). They’d agreed to answer a couple of questions from me, but once those questions made them uncomfortable, they became really, really angry. They asked me why I wasn’t answering their questions (more on that below), and became hostile.

This dude used the c-word repeatedly (claiming it wasn’t a bigger insult than calling a woman “a smelly bag of potatoes”, told a woman to violate herself with a cheese wheel (see above) and then said I was harassing him for asking this question.

–

- This was about power. I suppose I should have realized from the start that anyone who appears in your Twitter mentions to tell you that you’re fat, ugly, old and barren (“Who among us is NOT?” is my unanswerable reply) isn’t trying to have a conversation. They are simply trying to chase you off the platform, so your voice won’t be heard anymore. This dynamic became so apparent that I was actually able to predict when they would double-down on their insults, based on when I felt the power dynamic shift. A large number of them, perhaps in some effort to save face and regain a semblance of control, told me how excited they were about the project. Others tried to turn the tables on me, and tried asking me questions (most of them of the same insulting nature – asking who radicalized me to feminism, etc.).

(This was the same guy who accused me of harassing him above.)

Because their attempts to push me out of the space had failed, they were trying to gain control in another way. And when that, too, failed, they either turned to more insults, dismissed me, or blocked me.

—————

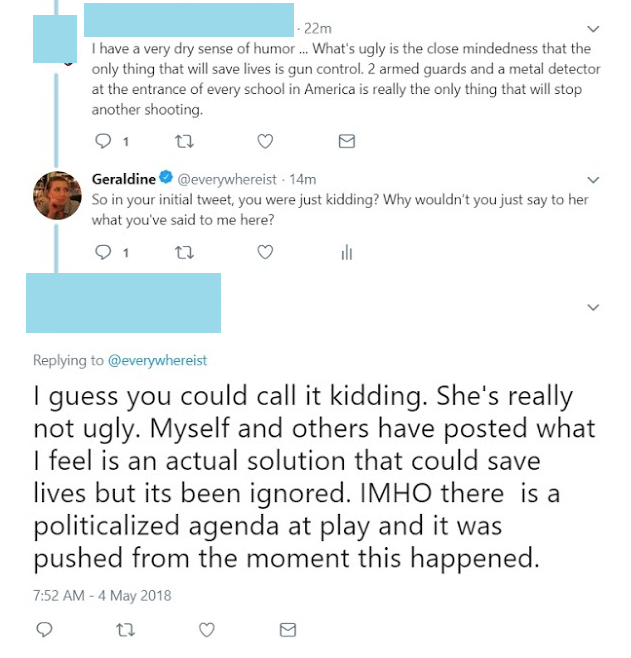

Since this experiment took place, many of the accounts I interacted with have been permanently suspended. Most of the others have blocked me after the fact (remember: I was simply asking them questions which they agreed to answer after they had initially insulted me. But that sort of thing can be scary, I guess.) Of all the conversations I had, exactly one left me feeling a modicum of hope. It was short lived. The individual I was talking to had been leaving insulting replies in Emma Gonzalez’s Twitter feed (this was before I realized I should probably only be engaging my own haters). Many of his comments included references to how ugly she was, and when I asked him about it, he seemed pretty embarrassed. He noted that she wasn’t actually ugly.

–

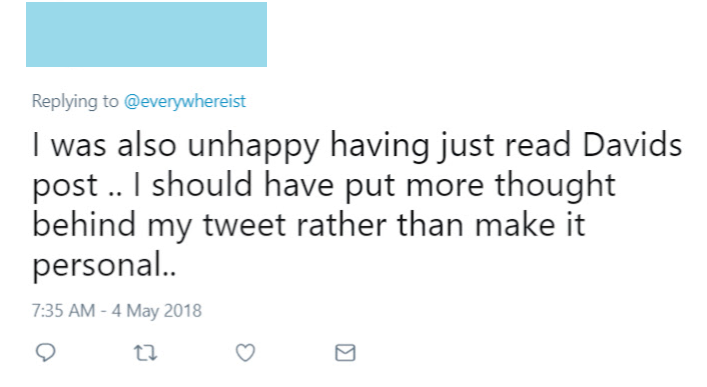

And that his personal attacks were not the best approach.

–

–

And while we disagree hugely on the gun control issue, I felt like our discussion made him realize that attacking a young woman who’d survived a mass shooting while at school was perhaps not conducive to his goals. I left our exchange feeling a little … optimistic?

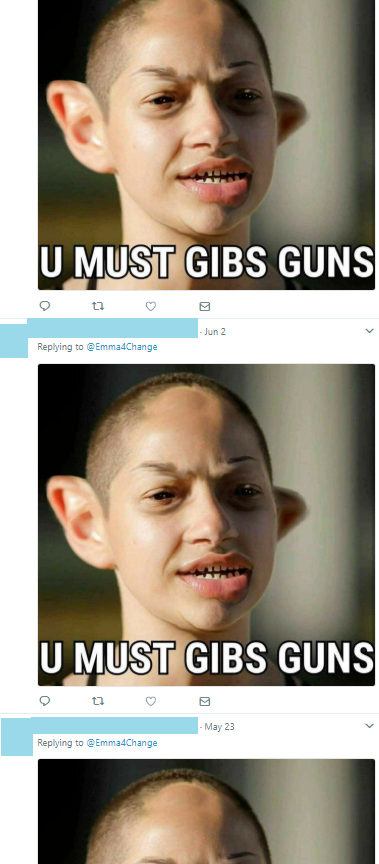

Today, I checked his Twitter feed.

It’s a bunch of personal, vicious attacks about her appearance directed at her.

So, yeah.

–

There’s a lot of discussion about how we need to reach out and talk to people who disagree with us – how we need to extend an olive branch and find common ground – and that’s a lovely sentiment, but in order for that to work, the other party needs to be … well, not a raging asshole. Insisting that people continue to reach out to their abusers in hopes that they will change suggests that the abuse is somehow in the victim’s hands to control. This puts a ridiculously unfair onus on marginalized groups – in particular, women of color, who are the group most likely to be harassed online. (For more on this topic, read about how Ijeoma Oluo spent a day replying to the racists in her feed with MLK quotes – and after enduring hideous insults and threats, she finally got exactly one apology from a 14-year-old kid. People later pointed to the exercise as proof that victims of racism just need to try harder to get white people to like them. Which is some serious bullshit.)

I spent days trying to talk to the people in my mentions who insulted and attacked me. I’d have been better off just remembering that when someone shows you who they are, believe them the first tweet.