Are Men Abused Online More Than Women?

(TW: this post discusses online abuse and includes screencaps and discussion of graphic, misogynistic, homophobic, and generally just horrifying language.)

I’ve been studying online harassment for a while now. I find myself a case study more often than I would like, and when I present on the topic, my slides are often screencaps of abusive Twitter replies that I’ve received. (My tweets get a lot of visibility, which is helpful for me as a writer and problematic for me as someone who doesn’t enjoy death threats.)

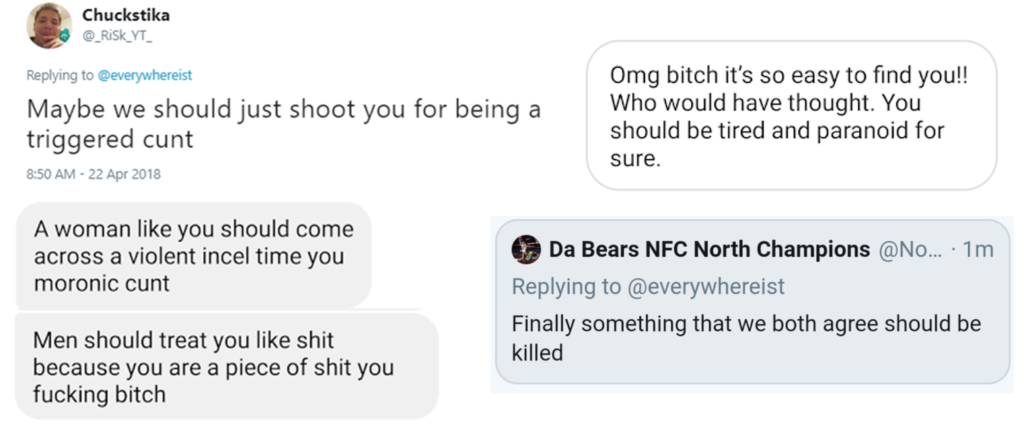

Tweets like these are in no short supply, and I realize that I’m hardly unique in this respect. Most women I know get comments similar to mine or far, far worse. On the spectrum of harassment, I’d put myself firmly middle of the pack. I’ve been told that I deserve to be raped, to be murdered, to have my body dumped where no one will find it so that my loved ones never get closure. But I’m a cis-gendered white woman with a lot of privilege on my side, so the vectors on which I’m attacked are, for unimaginative racist bigots, rather limited in scope. Generic misogyny, sometimes sprinkled with anti-Semitism (for some reason, everyone thinks I’m Jewish).

I’ve had 4-chan threads dedicated to me, with men commenting about how they can’t wait for when sex robots finally replace all of us, and how giving creatures like me rights was a huge mistake. People have recorded videos espousing their hatred for me and uploaded them to YouTube, videos that, disturbingly, receive thousands of views.

(I wonder, sincerely, where they find the time.)

And yet I have it easy – I know women in my industry who are so buried by hate that social media because largely unusable for them (a liability for any writer), who stop tweeting or posting because it simply isn’t worth it. Women who have auto-replies set up to their emails in order to help manage the sheer quantity of hate mail they get. Women who’ve spent thousands of dollars and had to move multiple times because they’ve been doxxed.

Recently, NYT conservative columnist Bret Stephens was called “a bedbug” by a David Karpf, a professor at George Washington University.

The bedbugs are a metaphor. The bedbugs are Bret Stephens. https://t.co/k4qo6QzIBW

— davekarpf (@davekarpf) August 26, 2019

Stephens responded by sending Karpf a letter, ccing the provost at his university. He was livid. He told Karpf that he was always amazed at what people said on Twitter about other people they didn’t know. “I think you’ve set a new standard.” His goal, it seemed, was to get Karpf fired, or at least professionally reprimanded.

When Stephens initially emailed Karpf and his boss, the tweet had zero retweets and 9 likes (at the time of this post’s publication, the tweet has 23,000 likes and more than 4,000 RTs). He later went on MSNBC and called the tweets “dehumanizing and totally unacceptable.” (He has since quit Twitter.)

I want to honor Stephens feelings (he must have been genuinely upset), but as someone who is constantly told that I am overreacting to death threats it’s hard to see a comment about bedbugs as dehumanizing.

One of the things I hear, time and again, when I mention online misogyny and harassment of women, is this: “Men are abused online more than women are.” It references a PEW study from 2017 of approximately 4,000 people across the United States. The study found that men were slightly more likely to be verbally insulted than women online. Women were more likely to received sexualized and gendered threats.

Rather than use this stat to illustrate that online harassment is an epidemic that we should all be dedicated to combating, I find instead that people use it to dismiss women who try to bring up the issue of online misogyny.

Men are harassed more than women are, so quit complaining.

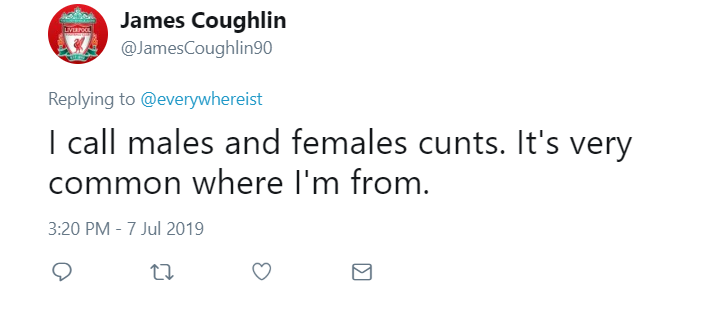

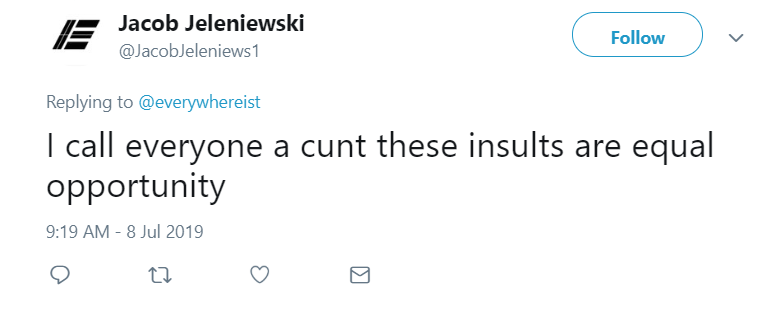

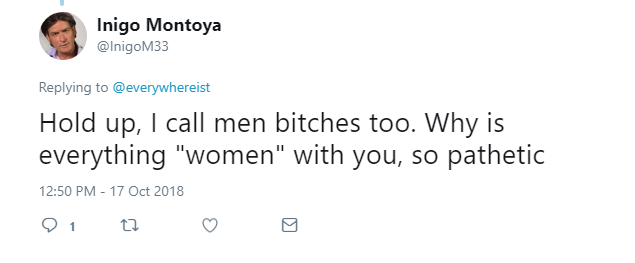

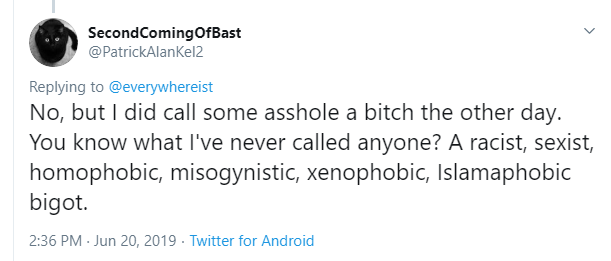

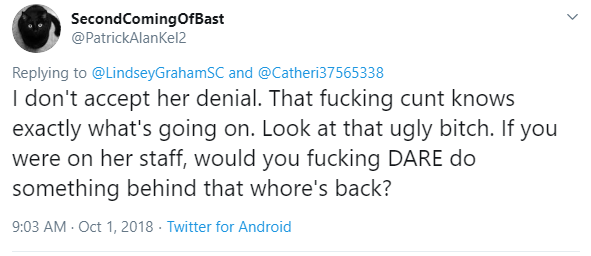

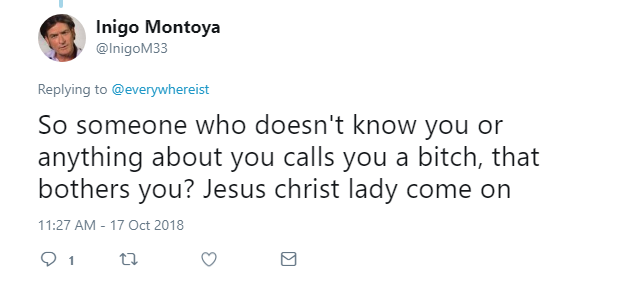

I don’t like to bring this argument up when discussing online harassment, because it creates a dichotomy that I think isn’t there. We can simultaneously care about the harassment of men as well as the harassment of women. In fact, the way in which many men are abused online is very similar to how women are abused – with feminizing and misogynistic insults. Men are attacked for being good advocates of women. They’re called bitches and cunts. When I spoke to the abusers in my mentions – part of an on-going project I’ve been undertaking for the last year or so – many tried to explain that they weren’t sexist because they called men the same names they called women. (The mental gymnastics required to understand their train of thought is exhausting. If you call everyone an insult based on part of the female anatomy, it doesn’t mean you are somehow egalitarian.)

If we truly want to address online harassment of men, then we need to acknowledge that at its root is the same thing we find with online harassment of women: toxic masculinity.

But Stephens wasn’t called a cunt. He was called a bedbug. And that ties in to the deeper issue I have with the PEW study: it has no objective metric to evaluate online abuse. The responders are the ones who determine whether or not their experiences constitute abuse. And that quickly becomes problematic. Because according to PEW study, one responder said that he was called a racist and a bigot, and that constituted abuse. And I heard that from several of the abusers I spoke to. This man (who’d effortlessly called me a cunt and then kept talking about gang rape in my mentions) said that he’d been abused by people online who told him that he was a racist, sexist, homophobic, misogynistic, xenophobic, Islamophobic bigot.

I repeat, this guy thought that being called a misogynist was abusive:

He was talking about Senator Dianne Fienstein

He thought being called a homophobe was abusive.

But he didn’t think he didn’t think there was anything wrong with calling women bitches or cunts. Another man accused me of harassment because I asked him if he considered himself to be verbally abusive. (This was after he’d called me a cunt.)

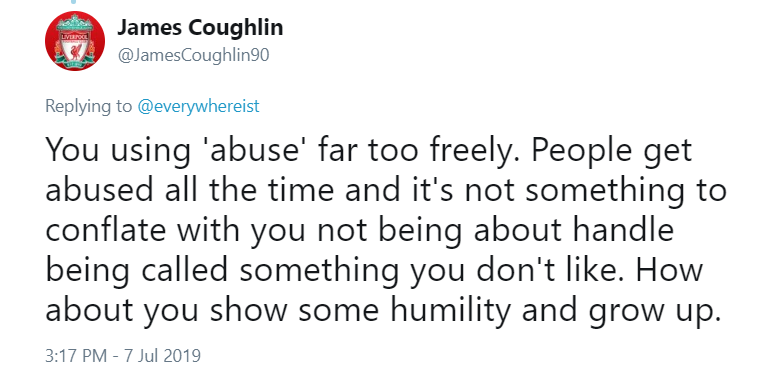

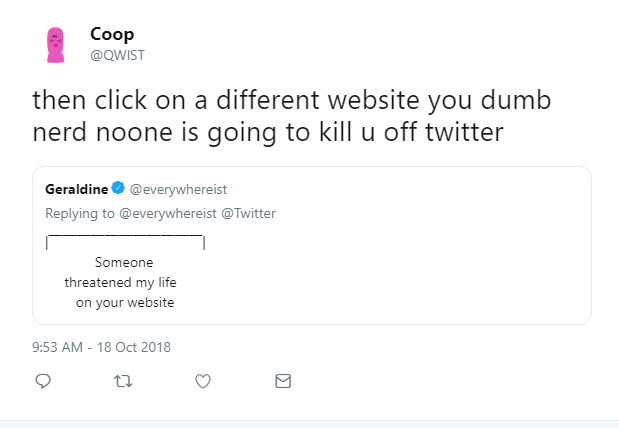

Abusers don’t realize they are being abusive. And when people call them out on their behavior, they think it’s harassment. This not only leads to overreporting of abuse by men who think their bigotry shouldn’t be called out, but it also risks women underreporting their own abuse. Because not only are women constantly harassed, but we’re constantly gaslit about it. We’re told that we brought it upon ourselves. Or we’re told that blatantly abusive behavior isn’t abusive. The guy who sent me this image was shocked that I found it offensive and said that it was in no way harassing or misogynistic:

Another guy told me that I was overreacting to being called a vile, man-hating bitch:

As a woman, the more you experience harassment, the more you are told it isn’t harassment. It’s enough to make you start to believe it. Maybe these death threats aren’t that big a deal. Maybe the rape threats are just jokes. Maybe I’m taking it too seriously. Maybe the problem isn’t what’s being said to me, but how I’m perceiving it.

This guy called me a cunt and said it didn’t count as abuse.

Are men insulted online more than women are? Or is misogyny so baked in that women aren’t accurately reporting or identifying the abuse that they experience? Because while Stephens was so angered by being called a bedbug, most women I know (and a lot of men, too, honestly) wouldn’t glance twice at a reply like that, much less write a letter to the boss of the person who wrote it.

I’d like to see a study that actually takes a sample of tweets sent to women and men and objectively evaluates them as abusive or not using a specific set of criteria. I suspect the results will be radically different. In the meantime, the answer to whether or not men are abused more than women seems to depend on who you ask.